Human threat to nature can be reversed

Human threat to nature can be reversed

In response to the newly released Global Assessment of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), CDKN's Shehnaaz Moosa and Mairi Dupar call for decision-makers the world over to seize the momentum provided by IPBES' startling science.

Earth's ecosystems have become so severely degraded that one million species are at risk of extinction and we are losing the natural systems that underpin human society itself. That is the deeply troubling message from the Global Assessment of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), launched this week.

The IPBES report is the most comprehensive assessment of the natural world ever undertaken. It is the work of 145 lead experts from 50 countries and 310 contributing authors over three years. It reviews 15,000 scientific and global sources and draws in unprecedented depth on indigenous and local knowledge of changes in nature.

The assessment finds that “the average abundance of native species in most major land- based habitats has fallen by at least 20 percent, mostly since 1900” and that “at least 680 vertebrate species have been driven to extinction since the 16th century.”

What is more, over 40 percent of amphibian species, almost one third of reef-forming coral species and more than one third of marine mammal species are now threatened with extinction.

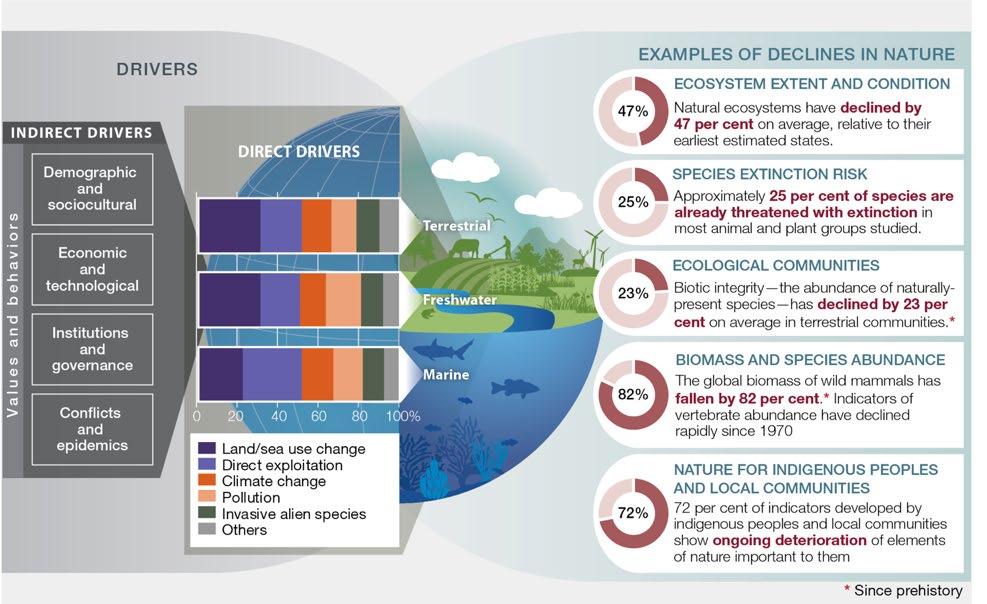

The top five causes of species extinction are: land and sea use change, direct exploitation, climate change, pollution and the spread of invasive alien species.

Shehnaaz Moosa, CDKN Director: Let us seize the momentum for sustainable change

The IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services is truly alarming. It finds that species extinction is occurring faster than at any time in human history, our biosphere facing ‘unparalleled change’.

It is right that the IPBES plenary – made up of government policy-makers and scientists – has called for deeply transformative changes in socioeconomic development to conserve and restore the delicate web of life that sustains us. Without changing our ways, Earth as we know it will continue to become sterile and depleted beyond our imagining.

Already seismic behavioural shifts have occurred around the world in recent years in response to the climate change crisis. These shifts show the possibility of deep economic, technological, social and cultural change for the planetary good. The acceleration of renewable energy innovation and investment to a point where renewable energy is expected to be consistently more cost competitive than fossil fuel energy sources by next year is a case in point.

There is no question that global transformation to reduce unsustainable levels of consumption and undertake environmental restoration is achievable. It will simply take a terrific commitment to public dialogue, education and awareness raising and a multi-layered, proactive response.

We can build on the momentum that already exists to combat human made climate change but do so from a more expansive perspective, which values biodiversity and the benefits of well-managed, well-functioning ecosystems.

With the IPBES report in hand, we have the guidance to embark on a new direction of travel that will enrich nature and ultimately, protect and preserve humankind.

Mairi Dupar, CDKN Technical Advisor: Ecosystem-based solutions to climate change can reverse biodiversity loss, too

Climate change is one of the foremost drivers of ecosystem disruption and species extinction in the world – according to the IPBES Global Assessment (see graphic, below).

Another top culprit is land use change.

Deforestation and the conversion of forests and other carbon-rich habitats, such as peatlands and grasslands, into agriculture and settlements removes precious habitats for diverse species, as well as driving up greenhouse gas emissions.

And so, it stands to reason that investing in the restoration and conservation of forests and other carbon-rich habitats can combat biodiversity loss and climate change at the same time.

'Carbon-rich' does not necessarily equal 'species-rich' though.

You can walk through a tree plantation where single tree species have been planted: where there is dry leaf litter underfoot and eery silence and stillness among the boughs without a bird singing, nor a butterfly flitting, nor a woman, man nor child calling.

Trees can suck up carbon – and also stabilise soils and prevent erosion with their root systems – so helping to both mitigate against climate change and to some extent protect against climate change impacts (absorbing intense bouts of rain and helping retain moisture in soils when there is less rain). Many tree-planting initiatives have even attracted climate finance on the basis that their benefits can be monetised – through carbon credits.

In a word, then, not all ecosystem-based climate schemes are created equal. The IPBES report notes that in some parts of the tropics and temperate zones, forest cover is increasing, but where trees are monocultures (single species), the consequences are very different and far inferior for biodiversity than the complex, native forest ecosystems that once stood there.

It’s possible to develop ecosystem-based solutions that provide this fuller host of benefits and avoid harm to people and biodiversity, but the solutions must be carefully conceived and locally-tailored, in order to succeed.

Luckily, ecosystem-based approaches to climate action are an important and growing area of focus by many local, national and international actors. A wealth of knowledge is emerging about ways to apply this thinking across rural, peri-urban and urban areas – and how such projects can deliver a range of ecosystem and livelihood benefits. Operational approaches can go ‘beyond carbon’ and ‘beyond income’ for a more multidimensional approach to ecosystem health and human wellbeing.

For example in rural Ghana, cocoa-growing is a pillar of the economy and rural livelihoods, but it is at risk from forest degradation and climate change. An Ecosystem Services for Poverty Alleviation (ESPA) project identified eco-friendly farming methods that could play a role in securing the crop’s future and enriching the health of the environment. Small holder farmers and the companies that buy cocoa are experimenting with eco-friendly practices (such as growing cocoa in shade under larger trees and intercropping, using mulches to attract pollinators and retain moisture) that could boost cocoa yields and will address some aspects of rural poverty. Policy changes at national level will also be needed to protect forests fully and allow cocoa forest systems to reach their potential for economic, social and environmental sustainability.

In peri-urban India, a project has shown how it is possible to nurture a healthy functioning local environment, and benefits for climate change adaptation, mitigation and food and livelihood security for people simultaneously. The Gorakhpur Environmental Action Group (GEAG) from 2012-2016 supported peri-urban farming in Gorakhpur city with the multiple aims of: “developing models of climate-resilient integrated agriculture-horticulture-aquaculture-livestock systems in small, marginal landholdings in the peri-urban context; enhancing the income and food security of the poor and vulnerable populations; ensuring the sustainability of peri-urban agricultural lands through different regulatory and incentive mechanisms; and enhancing the flood buffering capacity of the city as it expands, through the institutionalisation and replication of sustainable management of agricultural ecosystems.” (See also ‘Making the most of peri-urban agriculture’.)

Although ambitious, the project succeeded – according to independent evaluators – in “having a great and potentially lasting impact on the involved marginal farmers in the peri-urban areas. Farmers have been able to increase their income, as well as food and nutrition security, because of: i) reduced input costs and market dependency, ii) increased crop diversity, iii) improved ability to cultivate crops despite floods during the summer, enabling them to maintain three crops a year instead of one or two, iv) cropping intensification, and v) expansion of areas under cultivation.”

Approaches such as these – particular to the rural, peri-urban and urban areas where they have taken root but supported by nature-friendly national policies, can inspire the green shoots of new initiatives in other cities and districts worldwide.

There will continue to be a vital and non-negotiable role for protected areas in the landscape: swathes of land and ocean which – adequately protected – will be bastions of biodiversity. But, as IPBES Chair Sir Bob Watson said: protected areas alone will not be sufficient to stem the biodiversity crisis, “we need nature everywhere.”

As the IPBES Policy-Maker’s Summary concludes: “Nature can be conserved, restored and used sustainably while simultaneously meeting other global societal goals through urgent and concerted efforts fostering transformative change.”

IPBES has thrown down a gauntlet for policy-makers, producers and consumers the world over. We have the know-how to rise to the challenge if only we have the patience and breadth of vision. Now let’s do it.