Water will flow again from the sacred springs in the Himalayan rangelands

Water will flow again from the sacred springs in the Himalayan rangelands

In Nepal's Mustang rangelands, water scarcity prompts a community effort to revive sacred springs. Locals and migrant herders, together with the Rural Development Initiative (RDI), are co-creating innovative and resilient solutions. This holistic approach highlights the power of flexibility and cultural sensitivity to drive success. This story is part of a series celebrating the locally-led solutions supported by the UNDP implemented - Adaptation Fund Climate Innovation Accelerator programme.

The people living in the Mustang rangelands of Nepal know their lands well.

But less snow is falling and herding practices are changing, so the water that sustains their livestock’s fodder is waning.

Traditionally, herders had maintained sacred springs, known as chhuk bu, to water their yaks, horses, goats, cows and sheep. A chhuk bu can also be used for irrigation and drinking water.

Dane Carslon, speaking on behalf of the Rural Development Initiative (RDI) in Nepal, says the community needs to draw on new and old knowledge to ensure they have enough water.

With funding from the UNDP-Adaptation Fund Climate Innovation Accelerator (AFCIA), Carlson’s team have been facilitating community meetings to find solutions that draw on scientific expertise and the local wisdom of villagers and herders.

(UNDP-AFCIA accelerates innovative technologies, practices and business models for local adaptation through tapping into the incredible potential of NGOs, civil society, women and young innovators.)

During some of these community meetings, migrant herders shared the need to revitalise natural springs that had been buried under earthquake debris, or were fast disappearing due to a lack of maintenance.

The project team, community members and herders then developed some plans to revive the chhuk bu.

One group identified chhuk bu below a school building that could be joined with a water collection system for irrigation purposes. Another proposed a water feeding station that would allow animals to drink water without getting stuck inside the water bodies, potentially damaging the structure.

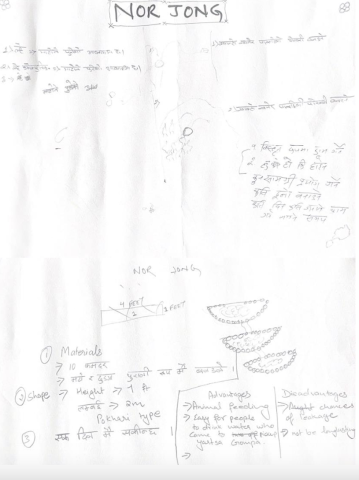

As per the illustration (above), the chhuk bu is located adjacent to the rock cliffs, by building two side walls. A wooden bar is then placed in between the walls. This wooden bar height is chosen in a way that restricts the animals to get inside the water bodies. (Sketch as per co-design workshop report compiled by Sonam Lama (project manager), Yungdrung Tsewang Gurung (field coordinator) and Sonam Dolkar (field assistant).)

Other co-design meetings looked at adaptations to repair or prevent trail damage after flash floods, as well as herder shelters for protection during severe weather.

These engagements were also an opportunity to address other pressing community issues around feral dogs, fencing and snow leopard attacks.

For water scarcity specifically, locals worked with RDI to detail the cost and quantities of the building materials, skills and labour that would be needed to implement their various prototypes and adaptations.

Carlson says that for him, the contribution of the migrant herders at these meetings was particularly important, because they are often the most vulnerable to rangeland decline. He says they have less access to social and economic resources than locals due to a caste system that puts them at the bottom of the social hierarchy.

“Many of the immigrant community members have come to this place because there are very few income generating opportunities anywhere else in the country,” says Carlson. Changes in rainfall patterns have forced migrant herders to seek work in the rangelands.

In fact, the declining fodder in the high rangelands has led to competition and social strife between locals and migrant herders. This situation, in the dry and picturesque Himalayas of Nepal, is yet another clear example of how climate change exacerbates underlying conflicts and brings negative economic effects to communities the world over.

Before organising the co-design meetings in Nepal, as a way to ensure success, the RDI team began researching people’s grazing practices back in 2022. They first looked into the community’s relationship with the landscape, and how vulnerable they perceived themselves to be to weather and fodder changes.

They had included a local community member from the upper Mustang in this field work, during which they interviewed several local herders, migrant herders, herd owners, hoteliers and traditional medicine practitioners known as ‘Amchi’.

They also conducted ecological surveys and built relationships with local governments and other local and international non-governmental organisations.

"The herders were able to demonstrate that they actually have a really important role in the future of this community, through the development of their own knowledge and their own work," says Carslon.

Carlson explains that the key to RDI’s approach here was creating a space for these herders to share their indigenous and place-based knowledge. By respecting and amplifying the wisdom of those who have nurtured and lived off the land for generations, communities that are already engaging in climate adaptation efforts are empowered.

This, says Carlson, works better than imposing top-down solutions and prioritising predefined measures of success.

“The RDIs involvement is more about innovating the process rather than the output. We're not trying to reinvent the wheel here," he says. "The intention is to acknowledge and give logistical resources, and financial resources, to communities that are already doing the work of climate adaptation on their own, rather than to insert our own agenda."

"The main challenge for us has been figuring out what are the relationships between two often distinct bodies of knowledge because there tend to be very tense relationships between herders and their bosses."

One other difficulty was aligning the project’s funding timeline with the natural rhythms and culture of life in a mountain village, so the RDI team had to be flexible with their project schedules.

During a time of water scarcity for instance, the team realised that the most helpful thing right then would be to step outside of the project’s goals and organise a water filtration system for the desperate community.

Carlson says this is a lesson for others working in this space to learn how to balance project objectives with the unique environmental realities of a region and the pace of life for the communities who live there.

RDI will also apply what it learnt in the rangelands of Nepal to future projects that aim to bridge the gap between scientific knowledge and local wisdom.

About this article:

This story has been co-created with the support of RDI, UNDP, CDKN, ICCCAD, and GRP, under the framework of the UNDP-managed Adaptation Fund Climate Innovation Accelerator (AFCIA).

The UNDP-AFCIA programme counts on financial contributions from the Adaptation Fund and the European Union and has awarded 44 micro and small grants to locally-led organisations across 33 countries worldwide, accelerating their innovative solutions to build resilience in the most vulnerable communities.

UNDP-AFCIA, is one of the funding windows anchored under the Adaptation Innovation Marketplace (AIM), a multi-stakeholder strategic platform that promotes scaled-up adaptation at the local level, launched by UNDP Administrator Achim Steiner at the Climate Adaptation Summit in January 2021.