Resilient housing: A flourishing sector

Resilient housing: A flourishing sector

CDKN's Miren Gutierrez looks at the potential for the prebuilt housing sector to increase the resilience of its products to climate change.

Modular, prebuilt homes are in fashion to the point that, in the United States, the demand for prefabricated housing is forecast to expand 15% annually through 2017, according to a 2013 report. Some of the expertise in the prebuilt housing sector is also dedicated to exploring new ways in which a house can withstand climate-related disasters.

The housing problem is no longer quantitative, but qualitative, according to the Global Compact Cities Programme. The organisation notes that “people tend to constantly improve and adapt their dwellings in order to better accommodate their changing needs.” Because housing is “a process, not and end”, say authors Sandra Moye-Holz and Constanza Gonzalez-Mathiesen in a report about Chile's case published by the Global Compact Cities Programme.

But what does it all entail? Do all hazards pose the same sort of challenges? Is resistance the same as resilience? Tuan Anh Tran notes in a book about “Developing Disaster Resilient Housing in Vietnam” that there is a lack of consensus in defining resilient housing and a gap in academic literature on this vital matter for many communities around the globe.

For example, with regard to flooding, one of the most destructive climate-related disasters, Planning Practice Guidance notes that “flood-resilient buildings are designed and constructed to reduce the impact of flood water entering the building so that no permanent damage is caused, structural integrity is maintained and drying and cleaning is easier”, while “flood-resistant construction can prevent entry of water or minimise the amount that may enter a building where there is short duration flooding outside with water depths of 0.6 metres or less.”

Picturing a flood-resistant house, one can think of most constructions along the channels of Venice, which are protected by double, water-resistant barriers. But what does a resilient house look like?

Under the Sheltering from a Gathering Storm project, with CDKN funding, the Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-International (ISET-International) –an organisation that works with local partners to build resilience— launched in 2012 a “Resilient Housing Design Competition.” It called for innovative storm resistant shelters for low-income households, and the winning model selected to be constructed was analysed for its resistance to typhoons, including strong winds and heavy rainfall.

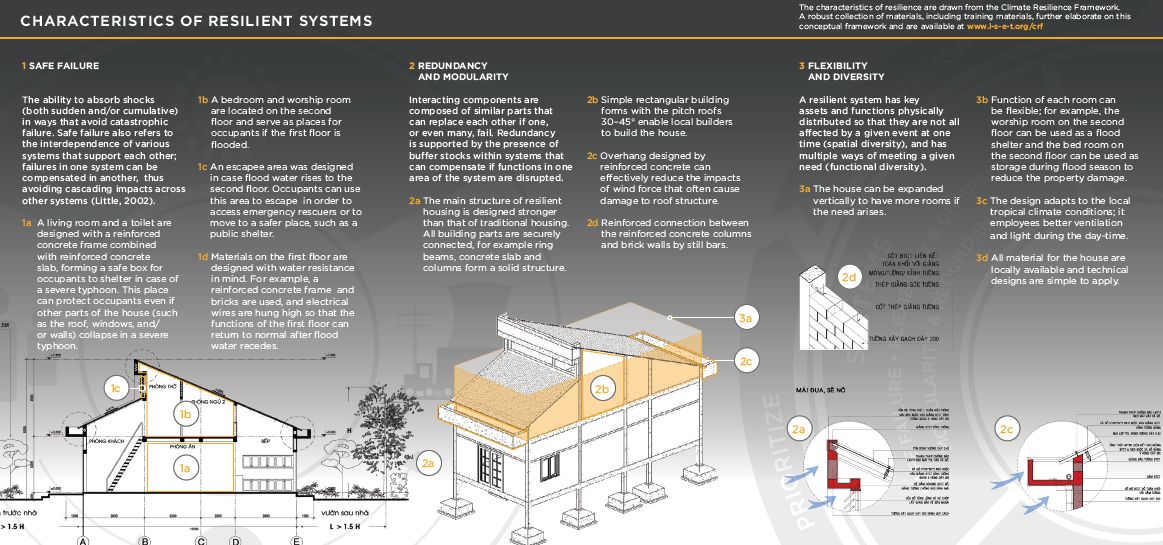

Characteristics of these resilient houses include: the ability to absorb shocks; reinforced spaces that can protect inhabitants even if other parts of the house are destroyed or flooded; escape gateways; the employment of water-resistant materials in sections that are likely to be hit by floods; redundancy and modularity that allow the interaction of different components of the building; solid structures; simple forms easily built locally with local materials; and a flexibility allows expansion and adaptation when needed.

(Double click on the graphic below to increase its size for ease of reading.)

Source: A CONCEPT OF RESILIENT HOUSING DA NANG, VIETNAM, ISET

The competition involved local architecture schools and professional businesses, and called for climate-adapted shelter designs that are low cost, technically effective and culturally acceptable; the best-judged shelters were the subject of the cost-benefit analysis research.

“Shelter accounts for the highest monetary losses in climate-related disasters and is therefore a significant cost for governments, the private sector and non-governmental organisations working on disaster risk reduction or post-disaster reconstruction,” according to findings from the CDKN project.

The Sheltering From a Gathering Storm: Typhoon Resilience in Vietnam – one of three case studies in this project— focuses on key issues related to housing and providing insights into the economic and non-financial returns of adaptive, resilient shelter designs that take into consideration hazards such as typhoons, flooding and temperature increases.

The two-year research programme targeting peri-urban areas in India, Vietnam and Pakistan –where cities face risks from typhoons, flooding and extreme heat— identified practical solutions for resilient shelters and the long-term economic returns of investing in such shelter structures. The project was led by ISET-International in partnership with Hue University (Vietnam), Gorakhpur Environmental Action Group (India), ISET-Pakistan and ISET-Nepal.

The Vietnam report concludes that some of the innovative housing solutions are affordable and economically viable, and replicable in other regions. In spite of this, since families with low incomes have limited resources, new public policies are needed to provide subsidies, promote micro-insurance, require multi-hazard construction standards, bridge low-income communities with experts, and improve awareness.

In Pakistan, in 2010, about 12 million homes were destroyed or damaged by heavy monsoon rains, according to a report by the Disaster Emergency Committee (DEC). This is especially serious at the household level, since “the shelter is often the single largest asset owned by individuals and families, and the failure of shelters to protect people from hazards is a significant risk to lives and livelihoods,” according to the CDKN project.

Resilient housing is even more important when post-disaster response and relocation is considered. According to HPN, “normally, only 10 to 20% of housing needs are met, frequently with temporary rather than more permanent housing. To cite a few examples: one year after Cyclone Sidr the number of dwellings built by aid agencies in Bangladesh (2007) represented 7% of need; in Padang, Indonesia, after the 2009 earthquake it was 14%; and in the Pakistan floods (2010) it was 2.5%.”

In Da Nang, Vietnam, the community was involved in the “Resilient Housing Design Competition and participated in voting for the winning designs. “This helped to create awareness of the possibility to build homes which could withstand recurrent storms at little additional cost,” says a CDKN guide[1]. A total of 244 climate-adapted houses were built. And the structures “withstood Typhoon Nari, which hit during the course of the project, and minimised human and economic losses compared with other homes.” The Da Nang city government has since introduced a policy that means all housing plans in the city should apply resilience principles.

[1] The guide's title is “What does it take to mainstream disaster risk management in key sectors?” And the Da Nang case is already part of the literature on the subject.

Image credit: DFID