Lives of the Lakes: The significance of indigenous knowledge in fostering community resilience in India

Lives of the Lakes: The significance of indigenous knowledge in fostering community resilience in India

Knowledge-Into-Use Award recipient, Rhea Shah, takes us on a photo journey with a community in Gujarat, India, which relies on indigenous and ecological knowledge for their livelihoods. As the area urbanises, this knowledge is being lost, so Aranya Design Studio is working with students to document these traditional practices to strengthen resilience.

This post originally appeared on Global Resilience Partnership’s website.

Jaishriben Parol is an indigenous mother of three, residing in a small indigenous hamlet in Sarodhi, a village in the Valsad district of Gujarat, in India. Sarodhi has a population of around 2000.

She belongs to the Tadavia clan, the clan of the lakes. The clan derives their name from the lakes that dot their lands around which their hamlets have existed for as long as spoken histories and songs go. Jaishriben’s life represents the lives of many of her Dubla tribe.

Colonisation has led to a loss of land and identity for her people. The region was plundered for timber from its natural teak forests, which led to the displacement of the tribe and a loss of livelihoods. The deforested land was replaced by privately owned orchards and the once independent tribe was forced into becoming agricultural labourers.

Like most women in her community, Jaishriben works as domestic help in a dominant-caste home in the village. A large portion of her day is spent taking care of her children and grandchildren, cooking and preparing meals and caring for her animals.

There are over 90,000 mango trees in Sarodhi. Despite being surrounded by lush fruit bearing orchards, the Dubla people, who are largely landless, still depend on the van-vagdo (wilds that surround the village and border the orchards) for supplementary nutrition, their livelihoods and medicine.

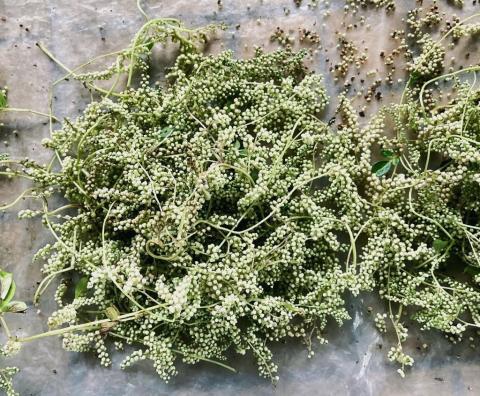

Dubla people fish in the lakes during the monsoon period and early winters and forage for nutritious seasonal greens, mushrooms and berries along the banks.

The Dubla people hold immense ecological knowledge about plants like the aakhdo, whose leaves release their medicinal properties when boiled with milk.These leaves are used in cures for leprosy, snake bites, tumors and intestinal worms. The latex is used to treat various skin diseases.

They also use the fragrant fresh leaves to line pots of umbadiyu, a winter delicacy of root vegetables cooked in an upside down earthen pot oven in the heart of a bonfire.

They also cook ulshi, the blossoms of one of the many types of dioscorea (wild yam). Ulshi is prepared into a spicy curry that is ideal to keep warm in the torrential monsoon cold.

As the village gets more urbanised, the banks of the lakes with their cool breeze and ventilation also form the social centre for people to meet and unwind.

Jaishriben’s home is an amalgamation of indigenous and modern construction and materials, flaking lime plaster covers brick walls built by the family and village. Giant brass pots blackened from cooking over wood fires sit in the corner.

They collect dried branches of trees and monsoonal shrubs after the wet season and dry them to create firewood.

Jaishriben and the women of the household are in her kitchen with the gas stove that they use together with the kitchen fires.

Jaishriben’s daughter, Niha, goes to the local village school. This is a government school with only two classrooms where students of mixed age groups study together.

The students are taught everything from math to music in these two classrooms, with minimal infrastructure and few teachers doubling up to teach multiple subjects.

It was evident to us at Aranya that it is these kids who still swim in the lake and walk the fields, who watch their parents forage and cook, who eat fresh and local, who inherit the rich indigenous ecological knowledge and traditional practices and who are key to the revival, protection and growth of these rich indigenous landscapes and ecologies.

We work with these students and communities to revive a faith in their own knowledge and practices and strengthen their relationship to their environment. We seek to learn from and share the wisdom that the community bears, using design to evolve traditional practices to cope with contemporary pressures.

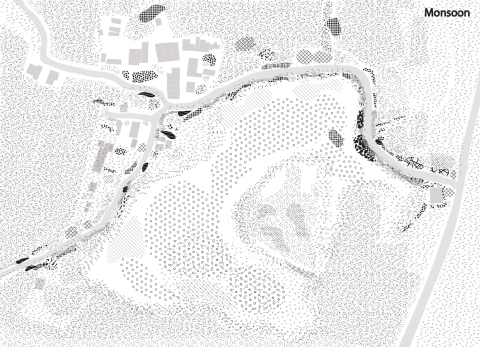

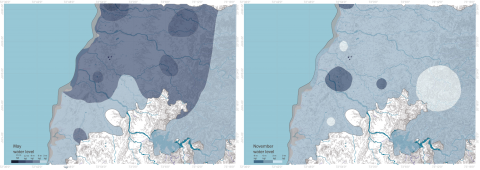

Over the past few years we have brought students from the city to map and document the village’s hydrological and food resilience systems. We engaged with the primary school students to share knowledge of their ancestors, which is fast being forgotten as the district industrialises and the landscape further erodes.

Our work traced the hydrological systems at the scale of the landscape, the wetness of a little patch of soil and inside a single leaf, to allow the students to situate their lives and lands in a larger geopolitical space and historical moment.

We have worked with educators from three local government schools to create a zine and activity book for students to learn about their indigenous knowledge and ecological heritage, while also learning about scientific methods to examine plants, soils, hydrology and landscapes.

As the students work on the activities they document foraged foods and related recipes, observe pollination, eat fruits and disperse seeds.

They learn about the infinite connections and interdependencies within different species in an environment while documenting and creating an archive of their families and communities’ collective knowledge and stories of landscapes and lives.

Aranya Design Studio is a young rural design and research studio in Vapi, a small city in the state of Gujarat, in western India. Aranya works at the intersection of landscape, architecture, art and ecology.

Vapi is a major industrial hub with chemical industries, named after a nearby stepwell meaning water storage. The villages near Vapi have lakes that serve as resilience systems to drought and flood by holding monsoon rain and slowly releasing water into the soil. The lake ecosystem also contains a rich plethora of wild food including fish and invertebrates, alongside wild aquatic plants, emergent macrophytes and herbs that are both nutritional and medicinal. However, rapid urbanisation is drawing more water from and releasing more sewage into the lakes which is destroying the lacustrine ecosystems.

Read more

Knowledge into use awards: #Art4Resilience

#Art4Resilience: Announcing the 'Knowledge into Use' award winners