The potential of climate change adaptation for agricultural enterprises

The potential of climate change adaptation for agricultural enterprises

There is tremendous economic growth potential for agricultural enterprises in East Africa, but expansion depends on their receiving appropriate support - including training on how to be climate-smart. Joseph Muhwanga and Teferi Demissie report. This is one of a series of blogs on ‘Accelerating adaptation action in Africa’ published by CDKN to frame the Africa anchoring event of the Climate Adaptation Summit, January 2021.

The role of MSMEs in East African economies

For African countries to achieve meaningful and sustainable development, the role of the private sector and its need for enhanced, adaptive capacity in the face of climate change is undeniable.

Many micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) are less likely to have adequate capacity to take the necessary measures needed to adapt to the potential risks and opportunities presented by climate change. Yet involving MSMEs is crucial as a source of employment, economic growth, social transformation and building resilience to climate change.

The definition of MSMEs varies slightly per country but the main parameters used are the number of people employed and turnover per year. In Kenya, the official definition of MSME is based on employment numbers whereby a) micro-enterprises have fewer than 10 employees, b) small enterprises have 10- 49 employees and c) medium sized enterprise have 50 to 99 employees. In Uganda, micro-enterprises employ up to 4 people and have turnover or total assets not exceeding US$ 2690, Small enterprises employ 5-49 and have turnover or total assets of US$ 2,690 -26,906 and medium enterprises employ 50-100, with total assets US$ 26,906- 96,863. In other jurisdictions, they talk of SMEs as having fewer than 250 employees.

According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistic (KNBS) 2016 MSME report, there are about 7.41 million MSMEs, 1.56 million of them licensed while 5.85 million are unlicensed. They contributed 33.8% GDP in 2015 and with 14.9 million people engaged. In Tanzania, there are around 3 million MSMEs contributing around 35% of the GDP, and employing 5.2 million people. For Uganda, MSMEs employ over 2.5 million people contributing over 20% of the GDP.

We may ask: how many of these MSMEs are agricultural enterprises? How many of these are women- and youth-owned? Across the three countries, there is no data that shows the exact number of agriculture-based MSMEs and their actual contributions to the national GDP or total number of people employed. However, KNBS 2016 MSME survey attempted to categorise MSMEs based on economic activity. In terms of MSME distribution by sex of ownership, the survey showed 47.9 % of licensed MSMEs are owned by males and 31.4% by female. For unlicensed businesses 60.7% are solely owned by females while for male-female partnership constitute of 16.5% for licensed and 6.4% of unlicensed businesses.

Agri-businesses in the East Africa region face a myriad of problems and some of them are sector-based. Despite the critical role agriculture plays in the national economies and people’s livelihoods, its potential is not fully realised due to a number of challenges, ranging from lack of adequate capital to unreliable markets to climate change.

Vulnerability to climate change

With regard to climate change, recent research findings done by the Climate Resilient Agri-business for Tomorrow (CRAFT) project in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania shows that the region has been experiencing rising temperatures, shifting precipitation patterns, and increasing extreme events, such as droughts and floods.

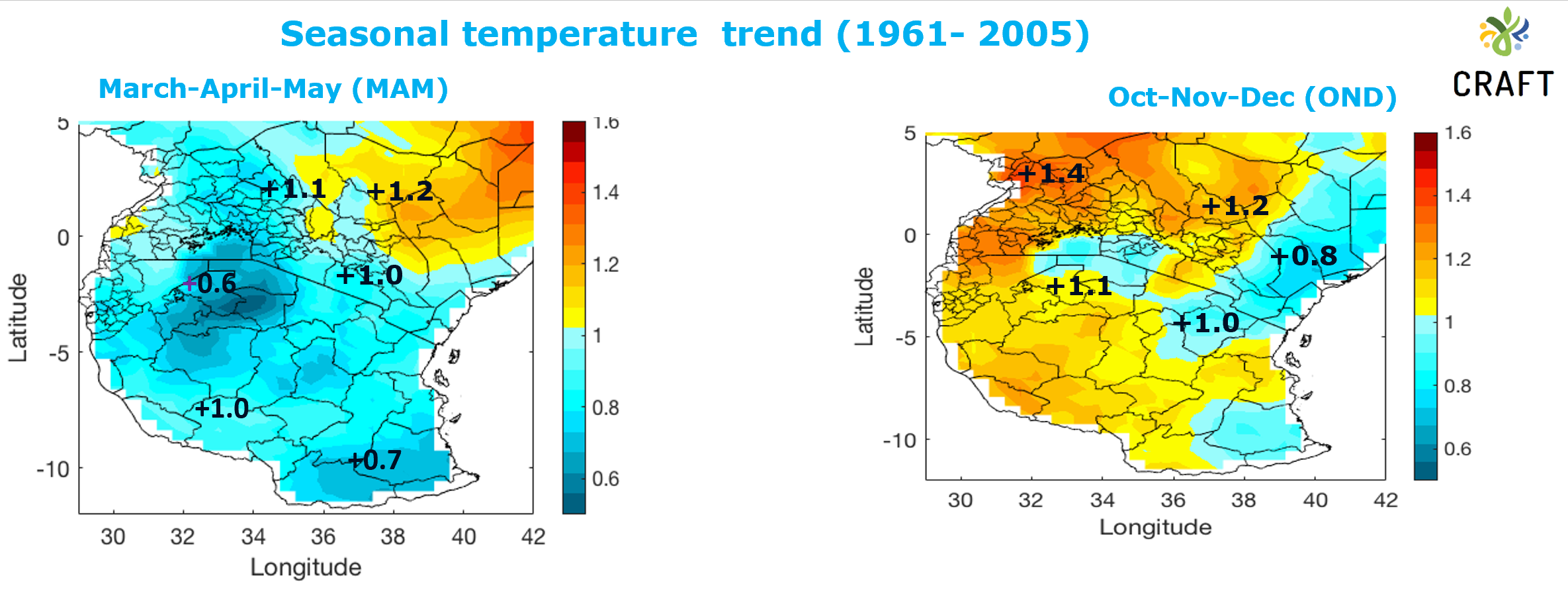

For example between 1961 to 2005, Tanzania experienced a temperature increase range of 0.6- 1.2 degrees Celsius, Uganda 0.7 - 1.4 degrees and Kenya 0.8- 1.2 degrees. See Figure 1:

Figure 1: Observed seasonal temperature trends (1961-2005).

Left panel: March-April-May; and right-panel: October-November-December. Source CRAFT 2019.

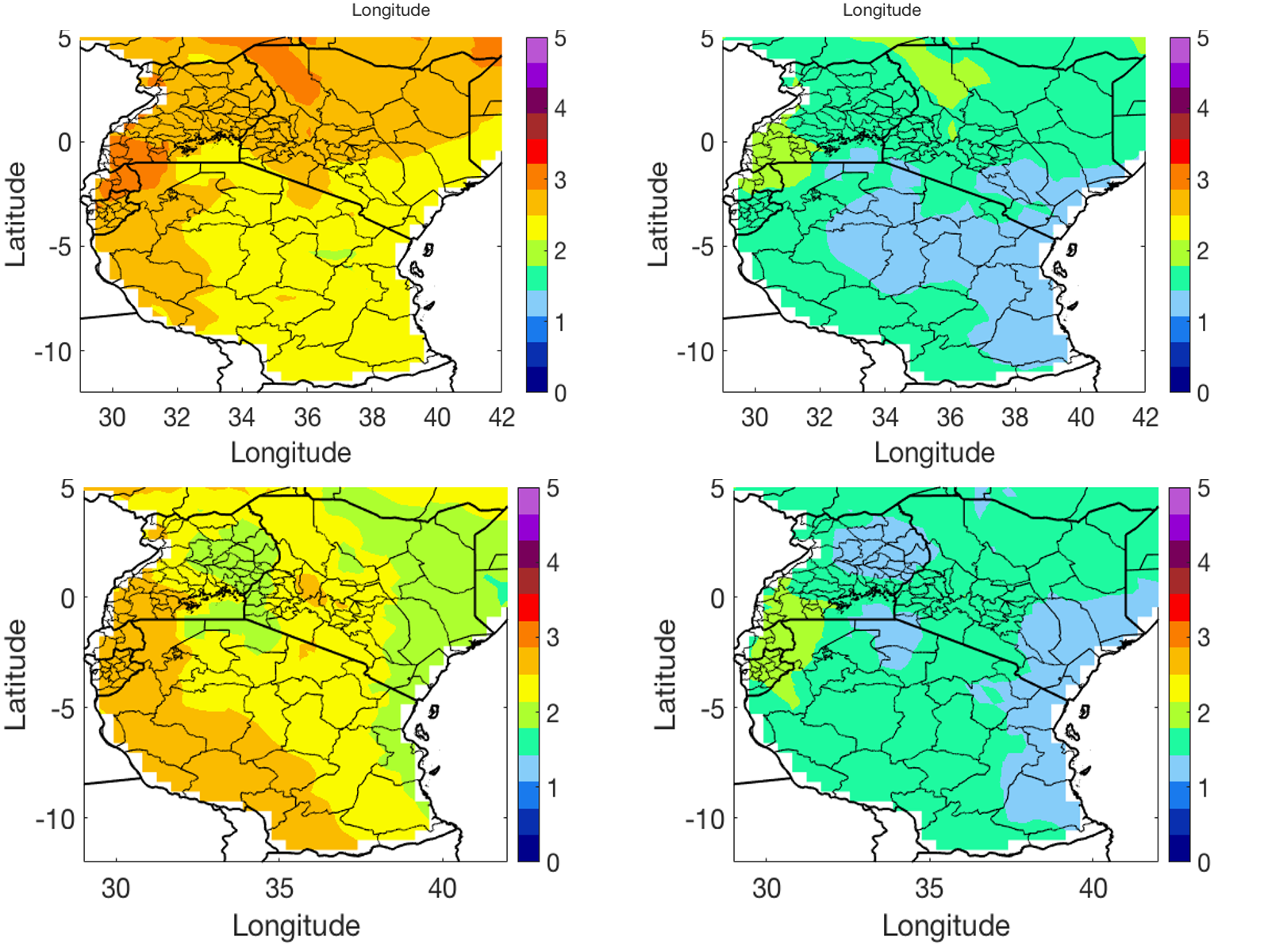

The study shows that, based on RCP 4.5 (a medium-emissions scenario) and RCP 8.5 (a high-emissions scenario) in the coming decades, many crop-growing areas will experience extreme events and seasonal shifts than they are used to. See figure 2 below. A similar spatial- temporal shift in precipitation has been observed across the three countries.

For example, in the Kenyan context average temperature is expected to increase by 1.4 - 1.8 degrees Celsius by 2030s and by about 1.8 - 3 degrees by 2050s.

Projections for Tanzania shows that temperature in the 2030s is expected to rise by 0.8 - 1.8 degrees while in the 2050s it will rise by about 1.8 - 2.8 degrees. The trend is similar for Uganda where temperature is expected to rise by about 1.8 - 2 degrees in 2030 and by 1.2 -3 degrees in the 2050s.

Figure 2: Temperature projections for 2030s and 2050s under RCP 8.5 (high-emissions, high warming) scenario.

Top: Temperature projection for 2050s for March-April-May (left panel: 2050, right panel: 2030s).

Bottom: Temperature projection for October-November-December (left panel: 2050, right panel: 2030s).

Average temperature rise for these months in degrees Celsius shown in the coloured key, on the right of each graph. Source: CRAFT 2019

What does this mean for agri-businesses?

The observed risks and impacts of climate change in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania will be widespread and unevenly distributed. The experts tell us that the cost of inaction may be up to 20 times more than the cost of investing in measures to adapt to climate change (see, for example, this CDKN study from Uganda). If the necessary adaptive measures are not implemented now by state and non-state actors the impacts will be dire.

On the other hand, climate change is all not gloom, there are instances where there will be beneficiaries of climate change. There will be opportunities that different actors can exploit.

To address these climate change related challenges therefore calls for designing appropriate interventions that target different actors of different value chains. Priority responses are:

- Adequate investment in climate smart agri-businesses (adequate finance); 2) Improving access to reliable markets, market information and marketing infrastructure (internal and external markets);

- Building capacity of agri-enterprises, farmers and extension providers on climate smart practices, technologies and climate services;

- Creating an enabling legal, institutional and regulatory framework and

- Supporting value addition. This has to be done through collaborative and participatory processes by all actors i.e governments, development partners, practitioners and private sector players.

What needs to be done? Top priorities for systemic change and scaling up

- Financing agri-business SMEs

Accessing affordable finance is one of the major factors that hinder MSMEs' growth. Traditional bank financing is available but not accessible (due to high interest rates, collateral etc) while private equity funds or government support is limited in the region.

The KNBS MSME 2016 survey showed that the main source of capital for 71.9 % and 80.6% of licensed and unlicensed MSME respectively came from family/own funds. Funds from banks was 5.6% and 0.8% for licensed and unlicensed businesses , non-bank credit institutions constituted 0.7% and 1.0%, while government loan was 1.0% and 0.0% , cooperatives was 0.4% and 0.0% , while NGOs was 0.1% and 0.1% for licensed and unlicensed businesses respectively.

Many of these businesses may never be able to repay these funds as their business could be negatively impacted by climate change. Therefore any efforts geared towards increasing agri-business (climate) finance will go a long way to increasing their sustainability.

Of importance to note, there should be a deliberate effort to only support those agri-SMEs that have a robust 'backward linkages' with other actors along the chain and have a large number of smallholder farmers. Integrating this with supporting other players who provide auxiliary services (e.g inputs providers, climate services and market information etc) will be paramount in helping achieve systemic change and scaling. The CRAFT project for example, has a grant fund available for such business champions in specific value chains.

- Enabling environment

Having a favourable legal, institutional and regulatory environment is a prerequisite for agri-businesses to thrive. Across the three countries there are multiple licences, taxes and levies – at national and regional/county level – that businesses have to pay. This greatly increases the cost of doing business. The private sector needs to be incentivised to invest and make their businesses sustainable.

A lot of advocacy will be needed to address multiple issues covering: the taxation regime, creating institutions that can support agri-businesses, access to agri-finance or climate finance, marketsaccess, access to climate services and information, value addition, renewable/clean energy, and others.

Development partners, donors, practitioners, governments, and private sector actors will need to work together to create better policies that will ensure adequate access to inputs, markets and finance for all actors along the value chains (both supply and demand sides).

- Capacity building

We are living in rapidly changing world. The business environment and technology is changing rapidly, thus the Agri-enterprise owners and managers will need to keep themselves up-to-date to remain competitive. Agri-businesses will need to improve their entrepreneur competencies, financial management, record keeping, embrace ICT and technology and climate services in their businesses.

According to KNBS 2016 survey, for example, the main sponsors for business trainings for licensed businesses were from: 50.6% self , 18.3% private business institutions , 9.3% other individuals , 5.4% government, and 6.7% from NGOs. For the unlicensed MSMEs: 52.7% from self, 18.6% other individuals, 6.6% NGOs, 2.7% from government.

This therefore demonstrates the need to factor in training needs in any agri-business support, especially on new technologies and innovations. This is especially so within the climate change space, if we are to achieve systematic change at scale. In the CRAFT project for example, capacity building on climate smart agricultural practices and technologies is a major component that includes among others jointly developing with the relevant national institutions climate smart technical manuals and training aid especially in value chains where this technical information is not available or not climate smart, for example sorghum, green gram, sesame, soybeans, sunflower, potato and common beans.

- Market access

One of the biggest bottlenecks negatively impacting on agri-business growth is lack of access to reliable markets –both internal and external. Supporting agri-business SMEs (the so-called business champions) that will have a pull-effort along the value chain –by proving reliable markets for other actors below the chain. e.g. aggregators, cooperatives, smallholder farmers , input providers, brokers etc will be crucial in unlocking the potential of the value chains at hand.

This should equally be tied to enabling environment, agri-finance and capacity building for varies actors along the chain. By doing so they will be able to meet the needs, taste and preferences of varies end-users/consumers (including niche market users) and thus maintaining the pull-effect and ultimately sustainability of their businesses.

About the authors: Joseph Muhwanga is Senior Climate Change Advisor, SNV and Teferi Demissie is a Climate Scientist, CCAFS and both working with CRAFT project.

Image: Ugandan farmer, credit DFAT.