‘Climate Smart Villages’ in Punjab, India provide lessons on climate smart agriculture

‘Climate Smart Villages’ in Punjab, India provide lessons on climate smart agriculture

Surendra Gautam and Keshab Thapa from Local Initiatives for Biodiversity, Research and Development (LI-BIRD), Nepal report on their field experiences learning about Climate Smart Villages in Punjab province, India.

The CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre (CIMMYT), and the International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) organised the ‘International Workshop on Climate Smart Villages’ in September in Ludhiana, Punjab province, India. LI-BIRD, in partnership with CCAFS is implementing the CDKN-funded ‘Scaling-up Climate Smart Agriculture in Nepal’ project and we took part to learn more about the Climate Smart Village approach.

The Climate Smart Village is a community-based approach to limit the effects of climate change through engagement with stakeholders on the best interventions that fit the local context. The idea is to mainstream climate-smart interventions into village development plans with the use of local knowledge through local institutions to address the triple challenges in agriculture - improving food production (quality, quantity and diversity), adapting to climate change and contributing to mitigating greenhouse gases emissions.

The workshop comprised theoretical discussions, field observations, and participant reflections, such as participatory assessment of portfolios of climate-smart agricultural practices for rice and wheat cropping systems to adapt to climate variability and changes, and farmer’s participatory evaluation of adaptation and risk management interventions.

The portfolio approach of Climate Smart Agriculture pilot projects proved to be very interesting. Farmers in Climate Smart Villages are using a range of technological and institutional interventions related to weather forecasting, index-based insurance schemes, efficient irrigation management strategies, adapted cultivars, and a range of other low greenhouse gas emitting options. In doing so, they are optimising synergies among adaptation, mitigation, food production and sustainable development.

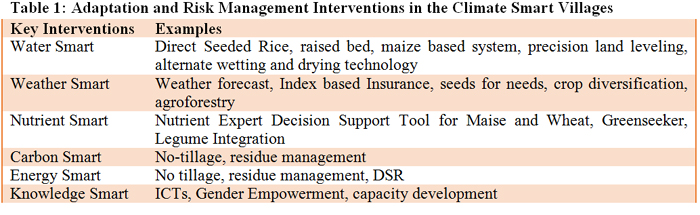

The table below illustrates examples of key interventions applied in the site through the portfolio approach.

Dr. M.L Jat from CIMMYT explained: “Nearly 50% of the cultivable land (of a total 1095 acres) of Noorpur Bet operate under climate smart practices.” He said that the process of identifying portfolios of climate smart agriculture practices in climate smart villages included joint effort of researchers (CCAFS and CIMMYT), local partners (BISA), and farmers (both male and female), with the major focus on reducing the workload of farmers by using direct seeded rice, use of happy seeder, greenseeker, and weather-based forecasts. Direct seeded rice eliminates the laborious manual transplanting of rice, reduces crop water requirement, and improves the soil condition.

Gender too plays a role in the process; happy seeding provides better working conditions for women, especially during sowing. Parvindar Singh, a soil scientist from the CIMMYT said, “Women of this village play a crucial role in the decision-making process and farmers of the village are not allowed to make any decisions on climate smart interventions without discussion within their family. Gender integration has become important part of the agriculture policies of Haryana. We, therefore, have prioritised including a gender component in all schemes of the climate smart villages.” Dr. Jat said that research was set under six different scenario comprising of no climate smart agriculture (farmer’s traditional practice), low intensity climate smart agriculture (up to two climate smart agriculture technologies), medium intensity climate smart agriculture (three or four technologies), and high intensity climate smart agriculture (more than four climate smart agriculture technologies).

Farmers applying high intensity climate smart agriculture practices (practicing minimum tillage by using zero tiller or a happy seeder, nutrient management by using greenseeker, managing irrigation by using tensiometer, and accessing weather information through SMS) feel confident in dealing with the effects of climate change. In addition, adaptive capacity has been strengthened through reduced cost of cultivation and input use, access to knowledge, information and technology, and reduced risk from drought.

The team also spoke with Gurpal Singh, a farmer practicing high intensity climate smart agriculture. He is using greenseeker, a new technology to measure nutrients in the crops and apply nitrogenous fertiliser in an optimum amount. “This tool is helping me to apply right amount of fertilisers. As a result, my crops are healthier with no overuse of fertilisers”, Gurpal told the team. Overuse of fertilisers, a major source of emission of greenhouse gases, and is common in rice wheat farming system of Punjab region. The team also observed rice farmers practicing ‘alternate wetting and drying’, which has the potential to reduce water use by up to 30% with the resultant cost savings for farmers. It is very useful during times of drought.

[caption id="attachment_56046" align="aligncenter" width="700"] The Climate Smart Village of Noorpur Bet, Ludhiana, India[/caption]

The Climate Smart Village of Noorpur Bet, Ludhiana, India[/caption]

In Punjab, CCAFS and its partners are successfully promoting 500 Climate Smart Villages in collaboration with the state government. According to Dr. Pramod Agrawal, CCAFS South Asia Regional Leader: “The aim of CCAFS to reach 10 million farmers is possible only after working in close coordination with national and subnational governments, civil society organizations, and research organizations to upscale whole package of climate smart interventions.”

Both of us felt that the workshop broadened our knowledge regarding new approaches to climate smart agriculture practices and portfolios - and that the techniques discussed have good potential elsewhere. Farmers making the right decisions through a participatory approach to climate induced problems will ensure future food security, a cleaner environment and improved incomes.

Pictures Courtesy: Surendra Gautam, LI-BIRD