Cape Town, South Africa: Strengthening policy support for climate adaptation and transformation

Cape Town, South Africa: Strengthening policy support for climate adaptation and transformation

Gina Ziervogel, University of Cape Town, highlights the need for community-level capacity building and knowledge co-creation for effective water management and adaptation to climate change. This is one of a series of blogs on 'Accelerating adaptation action in Africa' published by CDKN to frame the Africa anchoring event of the Climate Adaptation Summit, January 2021.

Globally, there are increasing calls for transformative adaptation to climate change. It is seen as key to meeting climate and sustainability goals – such as the objectives of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Sustainable Development Goals. In the context of climate change, transformative adaptation refers to the reduction of climate risk while simultaneously addressing issues of social justice and the root causes of that risk. Adaptation to climate change often takes place at a local level and there is a need to both build communities’ capacity to adapt and to ensure local perspectives are given legitimacy so they can be integrated into higher-level adaptation measures. For example, when considering adaptation to flood risk in a city, understanding the lived reality of residents in flood plains is essential to developing appropriate solutions.

In order to explore water service issues and potential adaptation options in low-income urban settlements in Cape Town, South Africa, a group of academics and community activists got together. Using a transdisciplinary approach, the project aimed to meet the needs of a local social movement, the Western Cape Water Caucus, who were looking for better evidence to support their arguments and actions when interacting with City of Cape Town officials around water related issues in low income areas. Many of the caucus members have been working to try and help fellow residents address concerns with high water bills, overflowing sewerage, water management devices that limit their daily water allocation and concerns around how to resolve water issues.

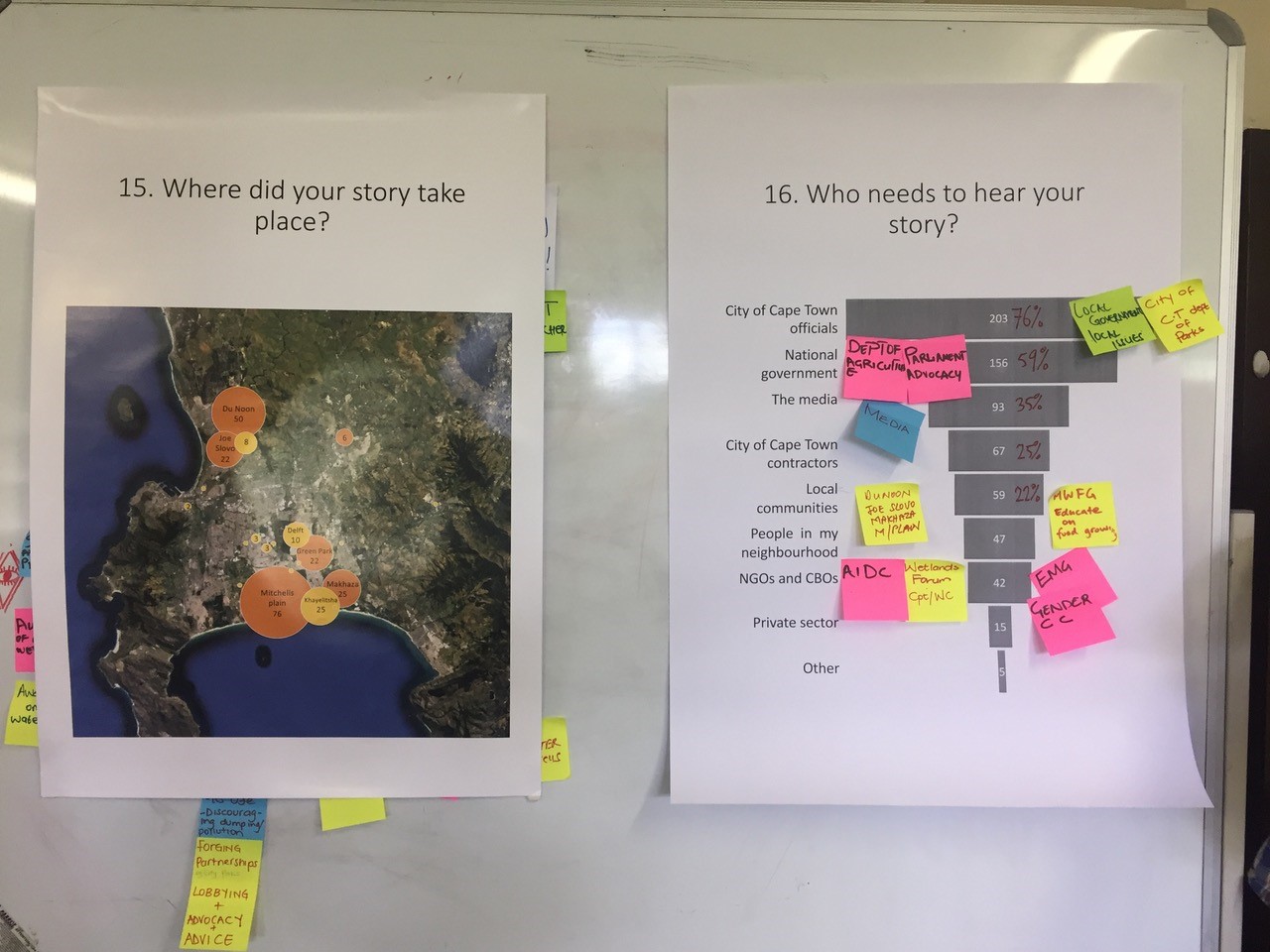

The project used a data collection tool called SenseMaker (Lynam, T., and C. Fletcher. 2015. Sensemaking: A complexity perspective. Ecology and Society 20) which requires the research team to develop a prompting question to elicit a short story from a respondent, followed by a series of follow-up questions to let the respondent ‘self-signify’ their story, to clarify what it means to them. The answers to the questions, developed in a four day workshop, are then collected on paper or via a smartphone app.

Three hundred and eleven responses were collected in the form of short narratives and quantitative data around addressing a water related issue in their community. Respondents then interpreted their own stories through a number of workshops and sessions. These findings were then presented to the studied communities and City of Cape Town officials. Activists and academics collaborated to help share the qualitative stories as well as quantitative evidence of themes that emerged across the sample. The most common issues that emerged were around bills and pricing, water management devices and leakages. Residents expressed a lot of frustration around battling to resolve issues and not getting help from the City officials. As one resident expressed, “My problem is a drain leaking inside my yard. My house has been built on top of a pipe, so I have to demolish my house in order to solve the problem. I went to the Housing Department and they told me that it’s not their problem.”

Capacity support can empower communities to better engage in policy activities

Since 1992, the UNFCCC has increasingly focused on capacity building, to assist mainly developing countries requesting support. One need that is often stressed is for capacity building at a community-level. Thus far, capacity building efforts through UNFCCC processes have mostly been ad hoc, and there is a need for international support for capacity building that is long term.

The SenseMaker process strengthened relationships between the City of Cape Town and the Water Caucus. The Caucus has subsequently been brought into city-wide policy and planning activities. As one city official said: “I actually came out of [the workshop] on a high. It was such a good encounter, such a positive encounter. I felt that the way the community expressed themselves was clear but not attacking. That was really positive for me.” Similarly it was an important project from the activists’ point of view, with one of them saying: “In the past, we had heard stories but they weren't documented. But now we have them documented so can use them to support our advocacy.”

Co-creating knowledge empowers communities and improves solutions

In order to mobilise capacity at the scale that is necessary to meet the climate adaptation challenge, it is important to consider shifting from a top-down transfer of existing knowledge, towards social learning and the co-creation of contextual understandings of how best to bring about change. If learning can be locally grounded and drawn from a broad set of knowledge systems, it can inform measures that support transformative adaptation and empower communities. Learning methods can be formal or informal and will be most effective when networks of trust in the community have been built up over time.

The SenseMaker project saw co-produced knowledge help to support an empathetic understanding of one another’s challenges, which shifted away from blaming and finger pointing and towards empowering individuals and organisations to better adapt to climate risk and water stress. The findings suggest that community-level capacity building could empower individuals and organisations to better adapt to climate risk and water service issues. This type of capacity building effort can better confront inequalities and power dynamics because of the opportunities to acknowledge and engage with locally relevant knowledge and knowledge systems. A transdisciplinary community-level project like this also has lessons for adaptation policy.

Improving equity and justice outcomes in adaptation policy

Targeted policy support that encourages community-level knowledge co-creation could enable more widespread, transformative capacity building. This is important for adaptation policy that aims to strengthen social justice. Approaches that co-create knowledge can help to legitimize knowledge of marginalized stakeholders. If this bottom-up knowledge is shared appropriately it can gain marginalised groups a ‘seat at the table’ for policy level discussions, such as how to develop future water sources, and enable local perspectives to be fed into higher-level adaptation measures. This type of approach can therefore help to address equity and justice issues as well as climate risk.

Read more blogs about accelerating adaptation action in Africa, for the Climate Adaptation Summit:

Images: Cape Town informal settlement and community consultations on water management, courtesy University of Cape Town