Enhancing direct access to the Green Climate Fund

Enhancing direct access to the Green Climate Fund

Introduction

The mandate of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) is to ensure different degrees of ownership by recipient countries through different ways (‘modalities’) to access funding, while promoting a country-driven approach. At the 3rd GCF Board meeting, held in March 2013 in Berlin, the different ways to access funding and the options for applying them gathered momentum. Board members agreed that “a country-driven approach is a core principle to build the business model of the Fund” and noted this as an area of convergence among its members.

Key messages

- The Green Climate Fund (GCF) Board must put ‘access modalities’ or the procedures and mechanisms for funding in place as soon as possible, so it can start disbursing funds for activities. In the meantime, it could consider the conditional, interim accreditation of institutions that have been accredited by other climate funds.

- The Board should learn from the experiences of others, particularly the Adaptation Fund and the Global Environment Facility (GEF), regarding how to provide developing countries with direct access to climate finance.

- The Board should note some of the particular barriers to direct access in the past – for example, difficulties in achieving fiduciary standards – and the need to build developing countries’ capacity in these areas.

- The degree of direct access to the GCF will also depend on each country’s ability to devolve decision-making power to the lowest effective level in its governance structure, at the national or subnational level.

Some Board members from developing countries stressed that direct access to the GCF is one of the key structures for country ownership. Under direct access, national governments or their nominated national and subnational institutions, receive international climate funds and disburse them to relevant projects. Developing country Board members argued for this access modality to be prioritised by the Board in the design of the Fund, including a provision for enhanced direct access (explained further on page 2). However, some developed country Board members argued that while direct access is important, it is one of several possible access modalities. The Board noted that the GCF should: “commence as a fund that operates through accredited national, regional and international intermediaries and implementing entities” (CCF/B.01-13/06), which leaves all options for access modalities open – including a larger role for multilateral agencies, for example.

This policy brief contributes to the ongoing debate around access modalities for the GCF.

In particular, it:

- explains the terminology around ‘direct access’ and ‘enhanced direct access’, outlining the competencies and capacities needed at each institutional level to achieve direct access

- reviews recent experience of using the direct access approach in international climate funds

- makes recommendations to the GCF Board and others.

Direct access and enhanced direct access: some definitions

Direct access is not a new concept in climate finance. The term was first introduced in 2007, in the decision to operationalise the Adaptation Fund, taken during the 3rd session of the meeting in Bali of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol. This decision defines direct access as the option for eligible Parties to directly submit project proposals to the Adaptation Fund, and for institutions (normally termed ‘entities’) chosen by governments to approach the Adaptation Fund directly.

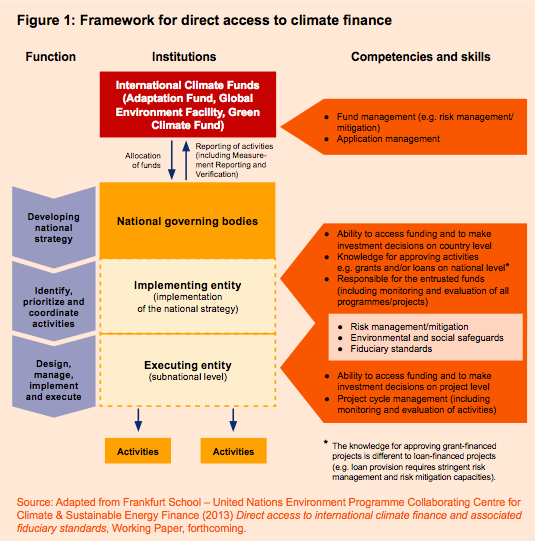

Funds are allocated and implemented at three main institutional levels: international, national and project/ programme. In the design of access modalities, it is important to consider how the different functions involved in accessing funds are distributed across the different institutional levels. At the national level, for instance, a government may appoint a ‘National Implementing Entity’ to apply for direct access to international climate finance (whereas at the international level, access to finance could be arranged via a multilateral agency but this would be considered an ‘indirect’ route); Figure 1 (below) illustrates the spread of actors and competencies that would be required for direct access at the national level.

Direct access to international funding means that the central functions of funding oversight and management are in the hands of domestic institutions, rather than multilateral or external agencies, but also operate under international guidance and rules. To date, National Implementing Entities with direct access to institutions such as the Adaptation Fund and the Global Environment Facility (GEF) have functions which are limited to oversight and management, while the final decision on the specific activities to be funded remains with the international governing bodies.

The term ‘enhanced direct access’ was introduced to the GCF to characterise a stronger devolution of decision-making, where both funding decisions and management take place at the national level.3 This is likely to require broader institutional capacities than under ‘ordinary’ direct access. Achieving ‘enhanced direct access’ is likely to require an evolution on the part of national climate finance institutions or national funding entities in developing countries.

Challenges and opportunities of direct access

Each country’s ability to gain direct access to gain direct access to international climate finance will depend largely on its institutional capacities. Some countries do not yet have domestic institutions with sufficient capacity to develop and implement project proposals. These countries will have to rely on international access, at least initially, with support from the international community to prepare for direct access if they so choose.

Some countries already have institutions with the proven capacity to develop and implement projects. This puts them in the position of being ready for direct access, assuming that they can also fulfil a number of other access requirements – some examples of which are given below. A country with the capacity to design a national climate strategy, make operational decisions (i.e. design projects and programmes) and allocate and manage climate funds has the potential to gain more autonomy by securing enhanced direct access.

Furthermore, the ability to devolve decision-making power to the lowest possible territorial level can result in more effective, inclusive and needs- driven access to resources. This does not stop at the national level, but goes down to the subnational level, including local government, civil society and the private-sector fund managers. It is important to develop and advance competencies step by step in relevant institutions. Analysing existing capacities and identifying where capacity should be built is an important starting point for increasing countries’ power to design and manage projects and take decisions.

Experiences with direct access

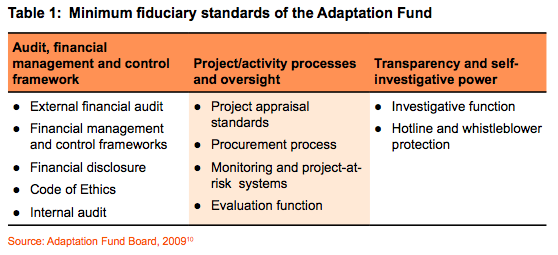

Decision-makers who are developing the GCF’s accreditation process and access modalities can learn from the Adaptation Fund and the GEF, two international climate funds with experience of direct access. Currently, both funds require high fiduciary standards, environmental and social safeguards, and experience in managing funds, as part of their process for accrediting national entities for direct access. Here, fiduciary standards are defined as: “trust in a person or business that has the power and obligation to act for another (often the beneficiary) under circumstances that require total trust, good faith and honesty”. With regard to climate finance, the term refers to financial integrity and management transparency and professional principles. As an example, Table 1 lists the minimum fiduciary standards for the Adaptation Fund.

Adaptation Fund

Under the Adaptation Fund, recipient governments can work with different access options, through a National Implementing Entity, a Regional Implementing Entity or a Multilateral Implementing Entity. To access the Fund, these entities must be accredited by the Adaptation Fund Board, which is responsible for the development and oversight of project implementation and monitoring results. If the recipient government chooses a National Implementing Entity, it will use the direct access modality.

National Implementing Entities can be national legal institutions, for example, a government ministry, a national climate finance institution, or independent institutions such as non-governmenal organisations (NGOs). The Adaptation Fund Board has stated that each eligible country should have only one National Implementing Entity.

Governments are expected to select projects and programmes through consultative processes and submit them to the Adaptation Fund Board through the National Implementing Entity. However, the Board takes the final decision to approve a project or not, based on a review process.

There are currently 15 accredited National Implementing Entities, including three from Least Developed Countries and two from Small Island Developing States. A further ten applications are under review. So far, six applicants have been formally denied accreditation because, for example, they did not meet fiduciary standards due to the incomplete lifecycle of a project or programme.

The Adaptation Fund Board identifies several key benefits of direct access modalities for the recipient governments: an increased awareness of the need for a strong and collective anti-fraud policy and a zero-tolerance attitude towards corruption; preserved institutional knowledge and enhanced internal management; and application of functions such as internal auditing, improved intergovernmental cooperation and dialogue with stakeholders.

Global Environment Facility

The GEF is the world’s largest funding mechanism for global environment conservation initiatives. It has worked for many years with a number of accredited multilateral entities, known as the GEF Partner Agencies. These are responsible for managing projects funded by GEF and assisting eligible governments and NGOs to develop, implement and manage GEF projects. Under the GEF-5 pilot project, the GEF stated that its aim is to accredit up to ten institutions as GEF Project Agencies, including at least five national institutions. The accreditation process consists of two stages: Stage I is a core value-added review and Stage II is an assessment of fiduciary standards. In 2012, the GEF received applications from eleven national and regional institutions for accreditation as Project Agencies; these have been partly approved to progress to Stage II. The applicants include four national institutions in developing countries that are requesting direct access. However, the GEF is still in the accreditation process and therefore not implementing direct access yet.

Challenges for developing countries in meeting direct access requirements

The challenges experienced by institutions in developing countries seeking accreditation under the Adaptation Fund or the GEF raise some questions for the GCF to consider. These institutions vary regarding their profile and competencies (see Figures1). There are existing environmental funds that are transforming into climate funds (e.g. Fonds National pour l’Environment, Benin); there are new entities that have been established for accessing and managing climate finance (e.g. the Indonesian Climate Change Trust Fund); and there are institutions that are diversifying and adding climate finance as one of their tasks (e.g. the Development Bank of South Africa and the National Bank for Agriculture and Development in India).

While 15 institutions have been accredited under the Adaptation Fund so far, many more are going through the process – some have been for a long time – and others have been rejected. The GEF has not yet accredited one national institution. Many countries face challenges in meeting the requirements:

- Developing countries often face challenges in preparing their institutions to meet direct access requirements, including the necessary fiduciary standards. After assessing applications for accreditation, the Adaptation Fund concluded that the direct access modality and the role of the fiduciary standards are not fully understood. Identifying the most suitable National Implementing Entities within a country is not straightforward.

- Countries face challenges in demonstrating the abilities required for direct access, even when they are capable. This is partly due to communication (and specifically language) barriers in case of the Adaptation Fund, which required that only key documents were translated from the national language into the Fund’s operating language of English.

- Some applicants to the Adaptation Fund and the GEF could not demonstrate sufficient experience in managing projects of the expected funding size, or the institutions were too young to document the successful completion of a project funded by a major bilateral or multi- lateral organisation. Furthermore, institutions lacked track records in demonstrating their ability to commit their own resources to GEF projects or to obtain co-financing.

- Applicants to the GEF often found it difficult to meet the criteria for Stage II of the application process, which called for close alignment with the GEF’s objectives and mission. For example, the GEF requires an extensive network of organisations and experts in the environmental sector at national and regional levels.

Implementing entities must go through complex steps, which consume time and resources, to fulfill the accreditation processes for these funds. Some institutions are unclear about how to align the fiduciary standards and requirement of different donors with their national laws and existing procedures. A more effective global approach for assessing institutional, technical and financial performance would be constructive. Recipient countries would benefit significantly from common requirements, such as aligned fiduciary standards.

Examples of meeting direct access requirements

Although achieving direct access is challenging, the following examples from Belize and Jamaica demonstrate how thorough preparation by the National Implementing Entities can lead to successful accreditation.

The Government of Belize established the Protected Areas Conservation Trust in 1995 as a statutory body to provide funds to support conservation and promote the environmentally sound management of natural and cultural resources. Selecting the Trust as Belize’s National Implementing Entity candidate was relatively straightforward, because it has credibility, good governance, transparency, and accountability. Following an internal review process to identify and resolve gaps in capacity, the Trust was accredited (with conditions) by the Adaptation Fund in September 2011. The required documentation included demonstration of a proper procurement process and associated monitoring system; for example, details of how to promote fair and open competition in the procurement of goods and services.

Jamaica was one of the first countries to secure accreditation from the Adaptation Fund. The Planning Institute of Jamaica, an agency of the Ministry of Finance and Planning, was approved as the National Implementing Entity. The Institute’s experience highlights the track record necessary for proving financial integrity and robust management, and the benefits of alignment with national legislation and structures.

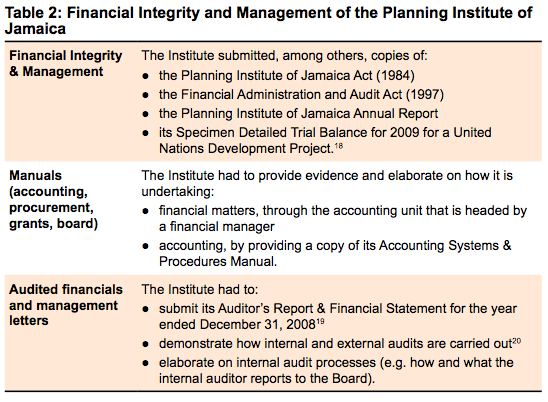

Not only does the Institute have a financial control framework, but also comprehensive audits and a code of ethics. The Institute’s funds are managed and disbursed under the Financial Administration and Audit Act, while its annual budget is submitted to the Ministry of Finance for approval and also undergoes an internal and external audit. Table 2 identifies some of the Institute submitted to the Adaptation Fund as part of the accreditation process.

Recommendations

How can countries ensure that they are ready for direct access under the GCF? Based on the above analyses, we make the following recommendations:

- Access modalities for the GCF should be defined as soon as possible. This will ensure that ongoing initiatives, such as national climate funds, can align with them, and help to focus and frame readiness activities and support to prepare recipient countries for these standards.

- The GCF should consider the experience of other international climate funds when developing the GCF’s accreditation process and fiduciary and other standards. Lessons learned from the Adaptation Fund and GEF, for example, may provide ideas for improving the accreditation process and for determining countries’ needs in terms of readiness support. There may also be lessons for the enhanced direct access modalities.

- A detailed assessment of the existing funds – particularly with regards to fund management, selection criteria and associated selection processes – is needed to document this experience. It should evaluate whether existing modalities allow for an objective decision-making process.

- Different types of institution have been appointed as National Implementing Entities. These different institutions and their varying capabilities need to be considered when developing access modalities. Each country should determine the level of direct access it can reach: ‘ordinary’ direct access or ‘enhanced’ direct access by which its institutions have more decision-making powers over the allocation of funding to projects.

- The GCF should consider accrediting institutions that have already been accredited through the processes described earlier. This could be done as a conditional measure, lasting until the Board has agreed its own accreditation criteria and modalities.

- There should be a transparent process for completing accreditation, for example, providing anonymous information about the submitted accreditations or detailed, non-confidential information about the accreditation application. This is currently a gap in the Adaptation Fund process.

In addition to direct access and enhanced direct access, which have been the focus of this paper, traditional access modalities – through international institutions – will be used by the GCF. If countries intend to pursue direct access in the future, the international implementing entities should assist them in building up the required capacities. This includes building countries’ ability to design and manage projects and take decisions at the most effective level – nationally or subnationally.

Download the full policy brief