The challenge of international climate finance in Latin America

The challenge of international climate finance in Latin America

Delivering the climate change mitigation and adaptation actions outlined in the Paris Agreement depends on the availability of funding. Many of the national climate plans, the Nationally Determined Contributions, have goals that are conditional on external funding. Yanina Paula Nemirovsky from Action LAC analyses some of the funding channels available for Latin American countries.

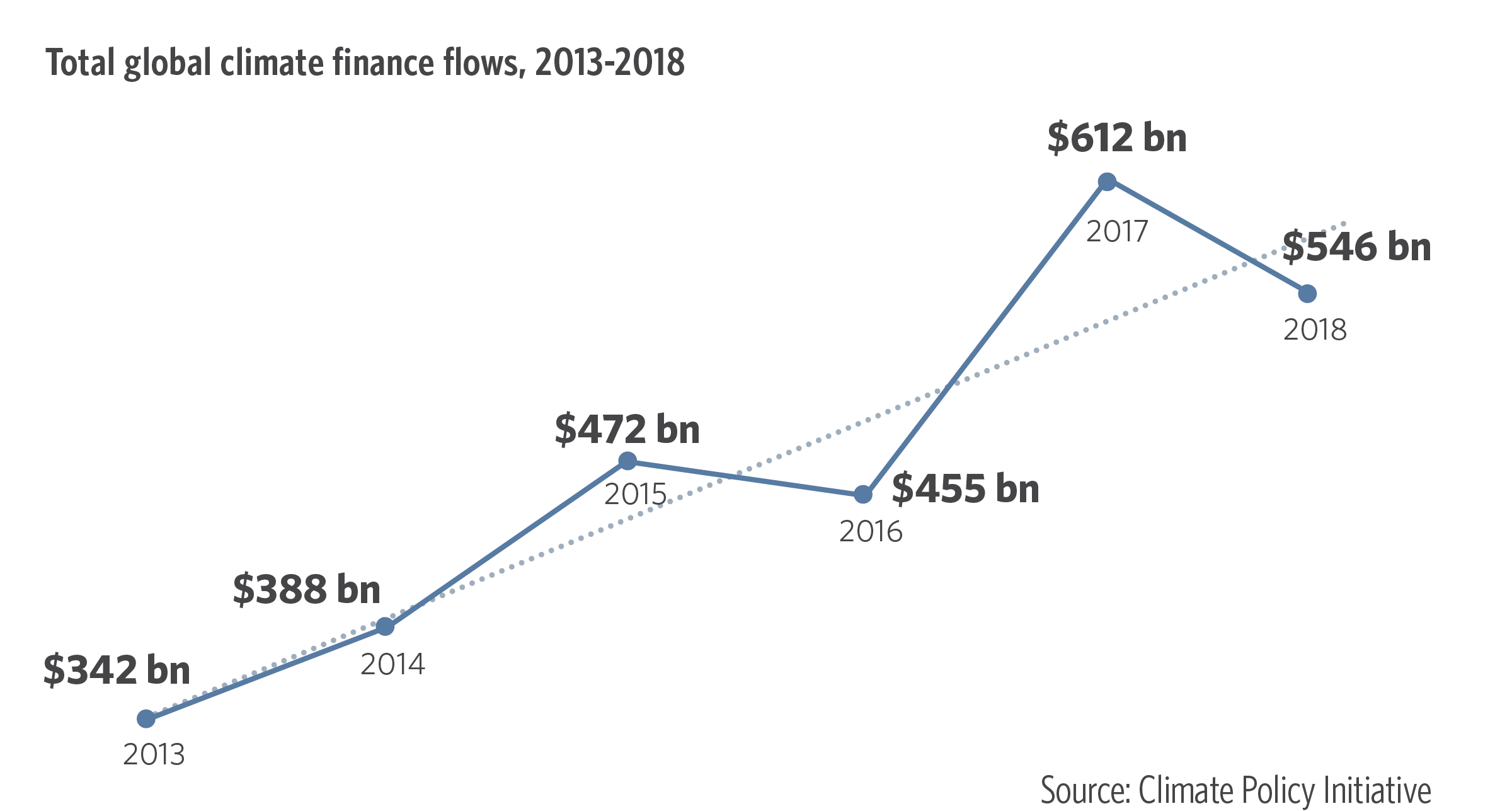

A major challenge in implementing the Paris Agreement centres on international funding. According to the Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2019 report, 76% of climate finance was invested at the source of the funding: investors favour local investment where the risks and opportunities are well understood. This figure, however, shows a decline from 81% in 2015 and 2016 which may be due to global efforts to mobilise financial resources across countries and regions.

This represents an opportunity for Latin America albeit within the context of uncertainty posed by the COVID-19 health crisis. Regional efforts to strengthen capacities for designing, implementing and monitoring NDC climate actions should be stronger than ever while there is still sufficient opportunity to do so.

Defining a starting point

Various criteria and guidelines have been put in place for identifying and calculating investment in climate actions and these are useful for institutions and organisations looking to access funding for mitigation and adaptation projects. Before guidelines were produced, it was difficult to streamline data: the various reporting mechanisms used different criteria and definitions and often included information that was unrelated to climate change.

The International Development Finance Club (IDFC) and the main Multilateral Development Banks (MDB) developed guidelines for classification of mitigation and adaptation funding. In 2015, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's (OECD) Development Assistance Committee also developed a set of guiding principles for monitoring climate change mitigation and adaptation action funding.

These principles define climate mitigation actions as those which ‘reduce or limit greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions or increase capture’. They then lay out nine sub-categories for action: renewable energy, efficient low carbon energy generation, energy efficiency, agriculture, forestry and land use, waste and sewage, transport, low carbon technologies, reduction of greenhouse gas emissions not linked to energy, and other cross-cutting categories such as clean industrial production, carbon capture and storage, policies and regulations and emission monitoring systems.

Recommendations are provided regarding allocation of finance to activities unrelated to climate change. It is important that accurate data is provided showing the amounts allocated to climate mitigation, particularly when they are integrated into larger budgets that cover non-climate-related activities.

By contrast, principles for monitoring the funding of adaptation actions are not similarly categorised. They are defined as follows: ‘climate adaptation actions include activities that tackle the current or anticipated effects of climate change’. Adaptation funding is based on three key requirements: The first is identification of risks, vulnerabilities and their possible impact related to climate change. Second, the means for addressing these risks, vulnerabilities and impact must be formally established in the project documentation. Finally, the project design must show direct links between the risks, vulnerabilities and impact identified and the actions that require funding.

Climate change funding in Latin America

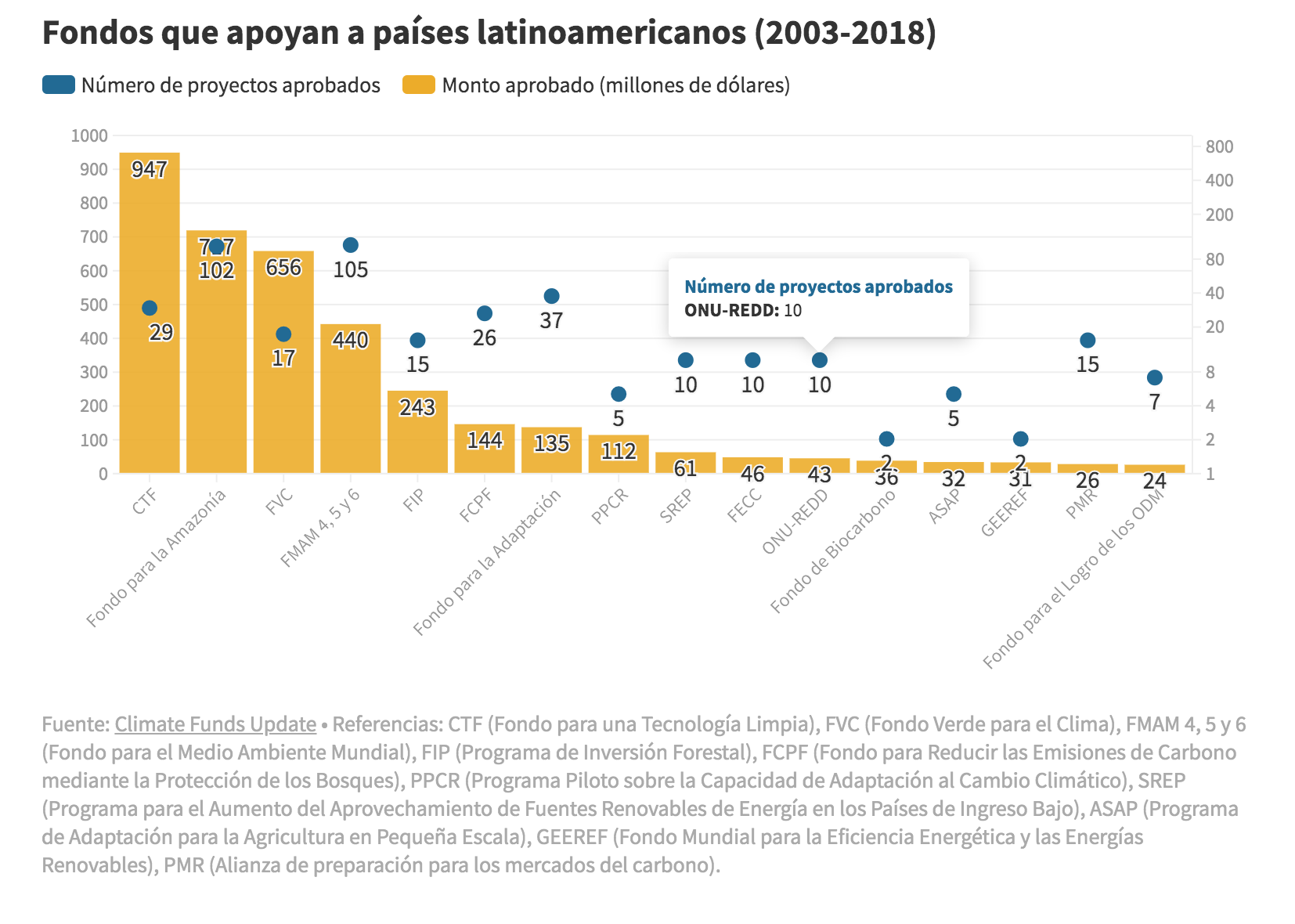

Multilateral aid to Latin America comes from four sources. According to the Regional Report on Climate Funding in Latin America, the main source of international climate aid currently comes from the Clean Technology Fund, a multilateral fund administered by the World Bank.

To date, this fund has allocated US$947 million to 29 projects in Latin America. The second source is the Amazon Fund which as funded 102 projects in Brazil amounting to US$717 million.

Since 2018, the Green Climate Fund (GCF) has been the third largest source of aid in the region, having funded 14 projects and three preparatory support programmes amounting to US$656 million in aid. The fourth source is the Global Environmental Fund (GEF).

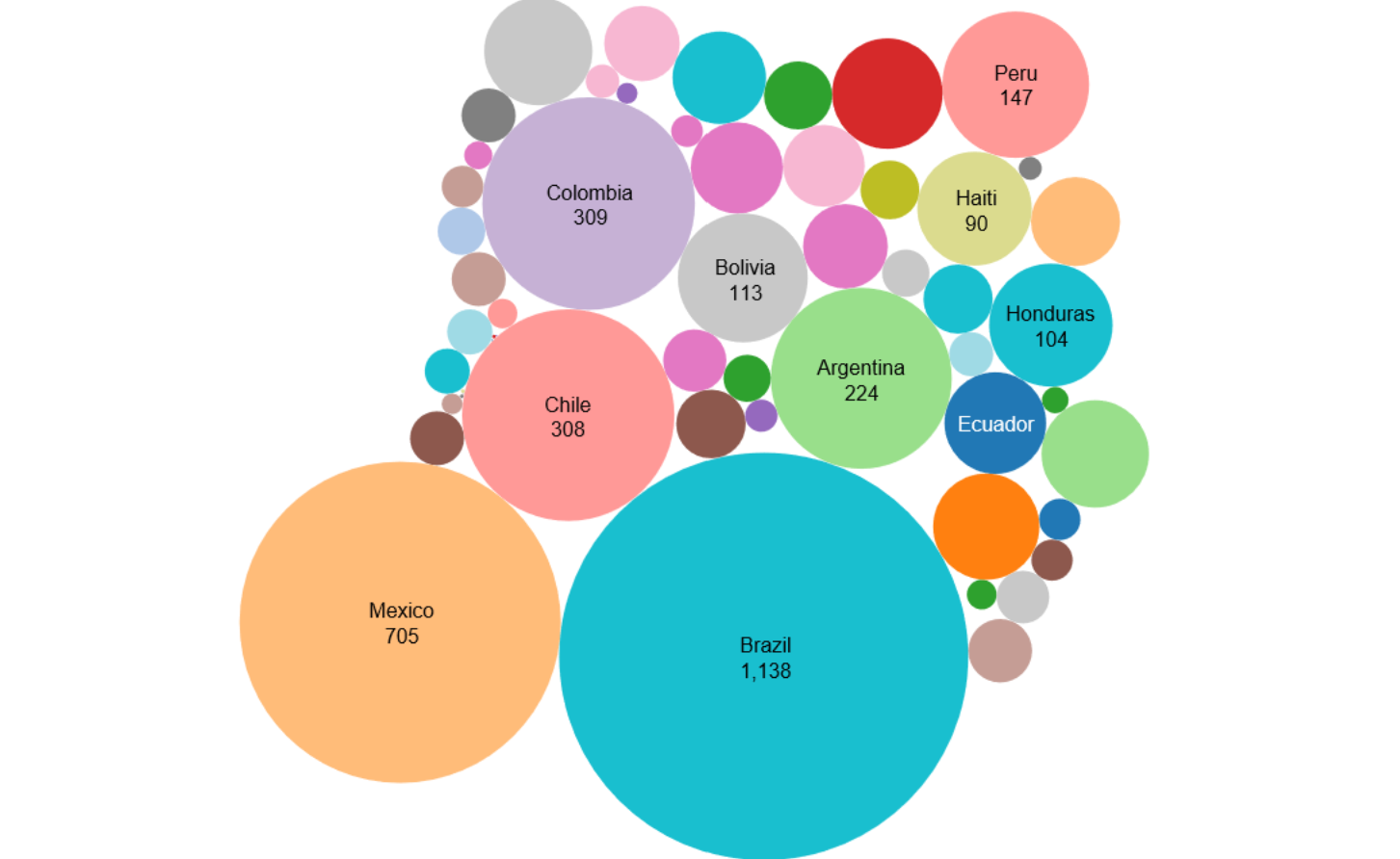

These four funds account for three-quarters of multilateral climate funding in Latin America. However, the recipient destination of these resources is highly concentrated, with Brazil and Mexico receiving 49% of the total.

Brazil is the main beneficiary of The Amazon Fund, the second biggest funder to the region. The other beneficiaries are Chile, Colombia and Argentina.

Diagram above: Funds that support Latin American countries 2003-18, showing millions of dollars of approved climate spending (yellow) and number of projects approved (blue) in Latin American countries

Although the goal is to ensure that funding to actions that address mitigation and adaptation is allocated equally, mitigation actions currently remain the focus of climate funding.

Andrea Rodríguez Osuna, Programme Manager at the Avina Foundation, explains that "mitigation funding can access different financial instruments as it can tap into the private sector". In contrast, adaptation funding is usually aimed at vulnerable communities and involves fewer business opportunities. This explains why most funding directed to adaptation actions comes from donations. Mitigation actions, on the other hand, can create opportunities for investment and employment with the result that the market focusses on these projects, in order to generate return. Adaptation actions provide little commercial interest and carry more risk.

Andrés Mogro, the National Director of the Climate Change Adaptation, Ministry of Environment, Ecuador, addresses this in his article Does the International Climate Aid Architecture Respond to the Needs of Developing Countries? He discusses the need to reformulate the current system of international funding based on the realities of developing countries.

Mogro says that “the current climate funding system does not respond to countries’ need for adaptation”. Funding of mitigation actions far exceeds funding of adaptation because investing in mitigation projects can offer financial returns for debt repayment. The current situation does not respond to developing countries’ needs, but rather focusses on debt acquisition and concessional funding.

It is very important to not only prioritise adaptation actions in budgetary terms, but also in terms of the future impact of climate change on other types of projects that are not exclusively climate related (and based on rigorous science). Suzanne Carter from the Climate Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) and Jean-Pierre Roux from Future Climate for Africa (FCFA) say in this adaptation finance blog that “there are ample examples of project proposals that either do not consider or insufficiently consider future climate impact, and this carries the risk of mal-adaptation”. With climate change, there needs to be a new focus on project design and climate should not be treated as an independent or isolated component, rather it should be considered an integral component of every project design.

According to the 2018 report by CEPAL, The Climate Change Economy in Latin America and the Caribbean, climate change impacts could cost Latin America between 1.4 and 4.3% of annual GDP. Climate change therefore provides an opportunity for us to transition into a new system, not just of climate but also socio-economic as we begin to approach problems less from a perspective of market profitability but rather one that prioritises humans and ecosystems.

Figure: Recipient countries of external climate finance, in Latin America and the Caribbean. Source: Climate Funds Update

International funding of adaptation

How much funding is required for implementing effective adaptation in the region and where could it come from? Estimates indicate as much as US$500 billion per year by 2050 (according to UN Environment) but this figure is not conclusive.

The Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) highlights how “difficult it is to provide a figure for adaptation funding which would be required under the scenario of 1.5°C warming compared to a 2°C warming scenario”. It also says that the main barriers to mobilising funding of adaptation actions are “the scale of funding required, reduced capacities and access to funding for adaptation”.

In the policy report, Funding Challenges for Adaptation to Climate Change in Latin America and the Caribbean, Virginia Scardamaglia identifies two main obstacles that national governments face when accessing international aid: project development and accreditation of entities.

Climate funders, such as the Green Climate Fund and the Adaptation Fund, follow complex processes for grant applications and require an exceptionally high standard of project design. They also often require that the entities applying for projects grants are accredited which is a complex process to complete.

National governments therefore need to develop the specific capacities that they currently lack. According to Scardamaglia, there is a “lack of human resources, both in numbers and in training on climate change issues and project development” which is preventing governments from accessing climate finance.

Various initiatives have been implemented to strengthen capacities in project design, with the aim of facilitating access to multilateral climate aid. One initiative is the Capacity Building Programme in Project Proposal Development for Accessing Climate Funding, this was undertaken by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), CDKN, Fundación Futuro Latinoamericano and other institutions. The programme has 10 modules covering the key issues for understanding international climate funding and developing projects that address the priorities identified in the Paris Agreement such as gender perspectives or indigenous people perspectives. The programme is also freely available to public and private participants.

One possible way to overcome these obstacles is through connecting civil society and national governments. This presents a great opportunity for civil society organisations and national governments to collaborate in project design, capacity building and implementation. The organisations already working on climate change issues have experience in design and implementation of actions and have a local presence. One such collaboration is with the Action Fund in Colombia, the first national entity to implement the project: Preparation for National Adaptation, which was funded by the Green Climate Fund. This collaboration assists in accessing funding for implementing the NDCs whilst also improving the government’s understanding of local issues, thus closing the gap between national and local policies.

Opportunity for collaboration

According to the Climate Finance Group of Latin America and the Caribbean (GFLAC in Spanish), for better understanding and decision-making by the countries that signed the Paris Agreement it is fundamental to define common criteria for classifying climate funding and to have a full understanding of global funding issues by taking into consideration both the interests of the donor country’s and the recipients.

GFLAC argues in the report: The Importance of Measuring, Reporting and Verifying Climate Funding in Latin America, that recipient countries should also play an active role in resource-allocation. These countries should also have their own mechanisms for measuring, reporting and verification of funding, that would make it possible to identify gaps so as to improve their fund-raising strategies for reaching the NDC goals. This would also help to build trust between those involved in allocating funding. Furthermore, it would make it possible for recipient countries to more accurately allocate local public funding to climate action initiatives.

The private sector should also be included in a comprehensive climate action funding strategy. The private sector provides funding but it can also provide valuable data for tracking national climate funding. GFLAC highlights the importance of measuring private funding to draw an accurate picture of the extent of private sector participation in climate action. For example, in 2019 GFLAC provided assistance to the government of Costa Rica in developing a system for measuring and monitoring private sector financing channelled through a regulated funding system to projects associated with climate mitigation and adaptation actions.

One of Latin America’s main challenges is that of climate action funding. To overcome this it would require that countries develop effective mechanisms for quantifying funding needs and prioritising areas for action in line with their NDC goals. For this to happen it is essential for all sectors of society to participate in the process. In this way, the concern around climate funding also presents an opportunity for generating processes and instruments that connect civil society, the private sector and government. In essence this is an opportunity to improve transparency in how funding is used and allocated. This is essential to ensure a climate-resilient future for everyone.

This article was first published in Inncontext by Yanina Paula Nemirovsky, as part of the project Civil Society Contributions to Latin America NDCs.