Policy coherence key to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals

Policy coherence key to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals

Patrick Curran, a policy analyst at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, shares new research on policy coordination across water, energy, food and climate goals in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia. He considers why countries at the latest High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development have agreed that coherent policy will be key to achieving the SDGs by 2030.

In July, representatives of 166 countries, civil society and international institutions gathered in New York for the High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HPLF). The forum happens every year to review progress towards meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This year the focus was on goals on water (Goal 6), energy (Goal 7), cities (Goal 11), sustainable consumption (Goal 12), landscapes (Goal 15) and partnerships for implementation (Goal 17).

Goal 17 specifically highlights the need for consistency across policy development and implementation – something that many countries struggle to get right.

At the forum, many progress reports prioritised energy, water and land issues, which practitioners call the water-energy-food ‘nexus’, and climate change. However, little time was given to Goal 17 and how to make policies across these sectors work together.

New research reveals weaknesses in policy coordination across water, energy and food

Despite a significant overlap among water, energy and food sectors, and the trade-offs and opportunities that exist amongst them, progress on aligning these sectors into coherent policy has been limited.

In almost all African countries, development will be centred on this nexus of energy, water and food, as the continent is poised to grow rapidly in the next few decades. These interconnected sectors will also be significantly impacted by climate change.

For instance, in many eastern and southern African countries there is a growing reliance on hydropower for electricity generation to meet increasing demand from growing cities. However, increased agriculture activity or land use changes in the watersheds that feed hydropower dams could limit the availability of water for power generation. These sectors are also highly vulnerable to climate change impacts – for instance, more frequent and intense drought conditions.

Despite this interconnectedness, research conducted as part of the Future Climate for Africa (FCFA) UMFULA project in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia reveals a lack of policy coordination across the water, energy and food sectors and climate policies. A score of 100% stands for optimal policy coherence; policy coordination in these countries scored 46–61%. Findings from Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy (CCCEP) indicate that these levels are also typical of countries of West Africa.

In presentations from 44 countries to the HLPF, or ‘voluntary national reviews’, only five highlighted how they were supporting processes to support policy coherence across sectors.

Timing an important factor for joined-up policy

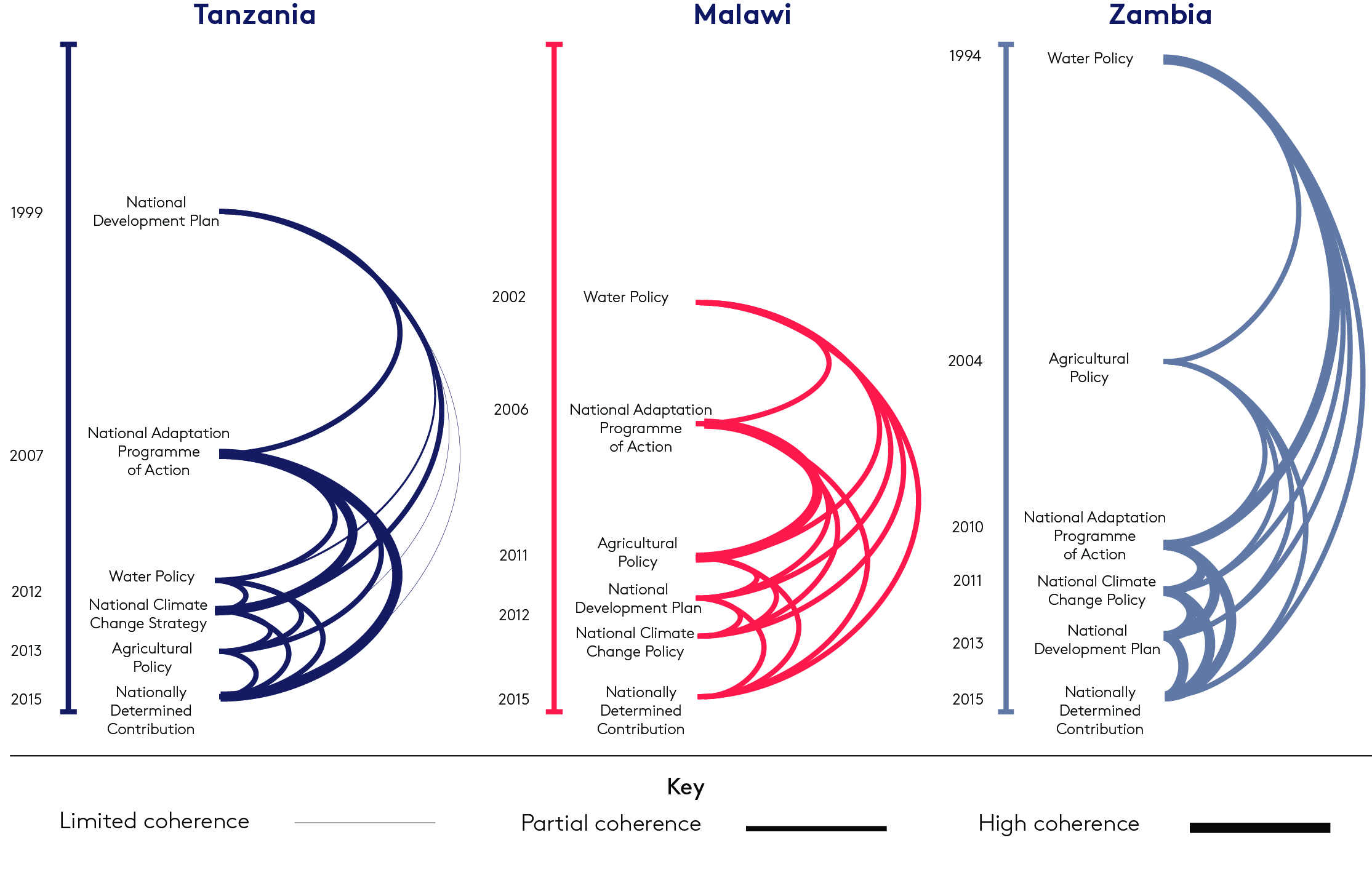

The research conducted in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia found that timing is particularly relevant for coherence (see figure). For example, in these countries there is a stronger link between National Adaption Plans developed in the mid-2000s and the suite of national climate change strategies or policies developed in the early 2010s. This implies that the earlier policies were used to inform those developed later.

However, coherence across sectors (called ‘horizontal coherence’) is generally weaker. For instance, policies developed specifically for the water sector can be reflected in national plans that span across both the water and agriculture sectors, although agriculture sector challenges have not been considered in their design. This is because sectoral policies are developed in silos and national plans are often compiled directly from sector-specific policies.

These problems can also be exacerbated as the science and understanding of the challenges facing different sectors evolve, and new policies are developed to address these challenges. Older policies end up misaligned with more recently developed ones, or with international commitments (such as the SDGs or the Paris climate change agreement) that include this updated knowledge.

Donor support can undermine coherent policy

A specific challenge for developing countries is that many initiatives rely on aid or donor financial support. This can unintentionally affect the degree to which policies are joined up because they often focus on specific sectors in isolation. Support can also come with time pressures for the delivery of policy against international or domestic milestones.

For example, the Development Plan of Zambia was revised in 2013 to explicitly integrate climate change (known as ‘mainstreaming’). Revisions were carried out under the auspices of the Strategic Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PDF), supported by the World Bank and conducted by external actors. However, the update overlooked the creation of processes that would also integrate climate change into national plans for the water, energy and food sectors. This left the development plan and sectoral plans, which sit beneath it, misaligned.

Cross-sectoral platforms can help to support policy coherence, but vary in effectiveness. For instance, in Malawi, the Vice President championed a cross-sectoral National Resilience Strategy, following extreme flooding in 2015. However, infrequent meetings, and the reliance on donor funding for the platform has limited its long-term effectiveness. Turnover of representatives and the resultant loss of institutional knowledge, also makes buy-in and the functioning of these sorts of platforms challenging in the long-term, especially in sectoral ministries.

Countries recognise policy coherence in achieving SDGs

At the end of the HLPF a Ministerial Declaration (PDF) was adopted that stressed that the 17 Sustainable Development Goals are indivisible from each other. Signatories recognised that “policy coherence and an enabling environment for sustainable development require engagement by all stakeholders and that they are key to build sustainable and resilient societies”.

The actions undertaken in the next five years will determine if we are able to meet the SDGs by 2030. The development and implementation of new policies will be essential, the time available to is increasingly limited. A central enabler to reaching goals will be processes that support coherent policy design and implementation (Goal 17).

As a first step towards achieving Goal 17, national development plans or policies should be reviewed, updated or developed, with the central objectives of integrating strong climate change action and meeting the SDGs. Following this, relevant sectoral ministries should use national plans as a guide to update sectoral policies.

This updating of policies has to be supported by the development of inter-ministerial and multi-stakeholder fora that can make decisions, and are sufficiently resourced to enable cross-sectoral discussion and coordination, such as Malawi’s National Technical Committee on Climate Change. Long-term commitment and leadership in this process is critical.

Refocusing country efforts on developing an effective process to support coherence is an essential next step towards meeting the sustainable development goals.

The views expressed in this commentary are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Grantham Research Institute, CDKN or its alliance organisations. This is an edited version of a blog which first appeared on the Grantham Institute website.

Image: Flooding in Malawi, photo courtesy UNDP.