Gender equity in climate finance – Why does it matter?

Gender equity in climate finance – Why does it matter?

Aditi Paul, CDKN Asia and ICLEI South Asia, argues that climate finance provides too good an opportunity to miss, as a vehicle for advancing women's wellbeing and development and righting some of the deep gender inequalities in society. She recommends how the design, delivery, monitoring and evaluation of climate finance projects could be improved to help achieve gender equity goals.

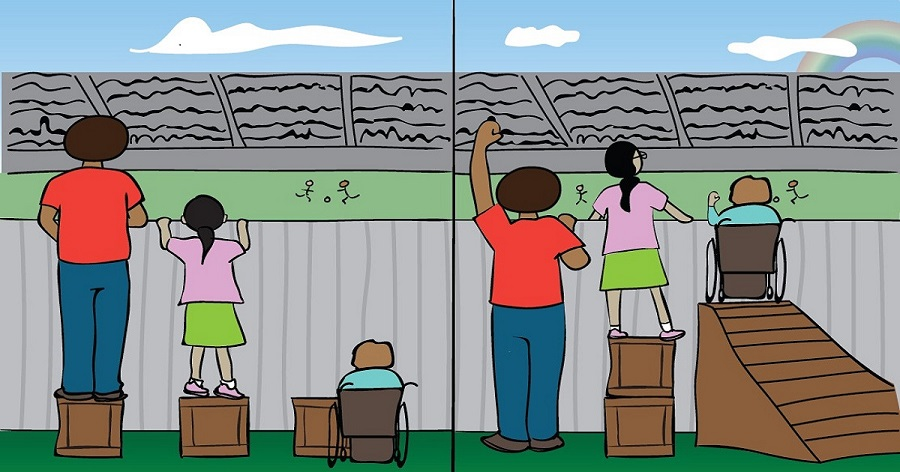

Women, who form the majority of the world’s 3.4 billion poorest people[1], are often disproportionally affected by the impacts of climate change because of discriminating societal norms and unfit policies. It is well known and accepted that women and men also contribute to climate change responses in different ways. The Cancun Agreement (2010) acknowledges gender equality and the effective participation of women in response to climate change, especially adaptation. However, given the fact that women are still disadvantaged in many societies, it is not just the question of equality but also of equity for them (see graphic, below).

Left: 'EQUALITY' Right: 'EQUITY'

Photo Source: http://muslimgirl.com/46703/heres-care-equity-equality/

Finance as a way to create opportunity for women

Climate change financing can create an opportunity to address long-standing gender equity issues. It can help facilitate and build upon ongoing processes of promoting equality, fairness, and justice in the global economy (UNDP, 2011). Recognising this co-benefit, a gender-sensitive approach to climate finance is increasingly being applied by the donor community.

The Green Climate Fund’s (GCF) “comprehensive gender-responsive approach” includes several references to gender and women in the fund’s governance and operational modalities, including on stakeholder participation and other discourse. The fund anchors a gender mainstreaming mandate prominently under its funding objectives and guiding principles.

Similarly, the Global Environment Facility (GEF) believes that more systematic inclusion of gender aspects in projects can create positive synergies between improved environmental impact and greater gender equality. Adopting the “Policy on Gender Mainstreaming and the Gender Equality Action Plan” in 2017, GEF has increasingly evolved as an institution that is gender-aware to one that is gender-responsive in its entire value chain of fund management – from designing to implementation to evaluation as well as raising awareness among its recipients, delivery partners and contributors.

These proactive measures taken on by international climate funds and donor agencies are forging a path for others to follow. Therefore, it would be wise for developed countries, which are currently mobilising billions of dollars to finance sustainable and climate-resilient development, to comprehensively enact gender equity.

Gender equity in public spending

Developing countries’ national public expenditure also forms a significant part of climate finance along with international and donor contributions. National climate funds, clean energy funds as well as indirect funding schemes all can contribute to either mitigate the impacts and or adapt to climate change.

But before we go in depth discussing the ways public expenditure can address gender equity while addressing climate change, it is important to understand the “gender-climate-finance connection”. This is because many fiscal economists may argue that fiscal policy should be gender neutral.

Let’s take an example from the agriculture sector. Women are the direct users and stewards of natural resources; especially in the areas of water, energy, and food. How? In the rural set-up, women are more responsible for securing water for the family and fuel for cooking.

In addition, women also work in the fields contributing to their families’ farm production, as well as to the country’s food security. Yet, they own less than 20% of the world’s land, lack equal rights to own land in more than 90 countries (GEF), and commonly face more barriers than their male counterpart in term of access to markets, credits, and training. Women also mostly remain underrepresented in decision-making spheres (UN Women).

Thus, when climate change impacts these resources negatively (mainly availability of water and energy), women’s lives are greatly affected. Policies and programmes through which the finances are channelled to address the issues on ground miss out on the gender angle. Indeed, many experts believe this disjuncture could cause entire policies or programmes to fail in meeting their objectives. This explains the critical role of finance, especially public expenditure, in equalising gender and giving fair opportunity to women to live and thrive in a better way.

Structuring public expenditure that could address the multiple objectives of a society/ community could be challenging, in terms of using scarce public funding in an equitable, efficient, and effective way. Addressing poverty, climate change and gender equity in one go is a tall order.

So, what are the mechanisms that different tiers of government should embrace to make people-centred policies and programmes, such as jobs created, health protected, energy distributed, be more climate resilient and gender equitable? Important strategies include:

a) Develop a nuanced understanding of gender equality/equity among all levels of governance. Also, there should be institutional ability to perceive the converging points of three separate policy outlooks, i.e. climate, gender, and finance. National, sub-national and even local government institutions demonstrating these capabilities are likely to better align their budgetary goals to the real needs of climate change and gender equity.

b) Create an interdisciplinary team of planning experts who not only understand the process of integrating climate change and gender issues but also have applied knowledge from field – what works and how.

c) Make good use of national-level climate finance mechanisms, such as national climate funds and ensure they are addressing climate change in a gender-sensitive way. This includes national entities (such as accredited entities of the GEF, GCF, Adaptation Fund) which help countries manage, coordinate, implement and account for climate finance.

d) Set a gender-responsive budget for development programme and project levels. Assess the budget through a gender lens and identify the impact of the various expenditures on women and men with the aim to create more equitable delivery of services. (NB Watch this space on forthcoming, user-friendly ‘how to’ guidance on gender-responsive planning and budgeting” from CDKN, and meanwhile, see the UNFCCC technical paper for tips.)

e) Explicitly mention the co-objectives of addressing climate and gender and inclusion in relevant performance indicators and results measurement frameworks;

f) Undertake periodic audits to ensure enforcement as well as to understand what works and why and feed-in findings to other sectors (including infrastructure, environment, and macroeconomic policy); and finally

g) Encourage a paradigm shift in climate finance thinking so that the needs and priorities of women, become a priority in approving climate investment projects.

[1] Nearly Half the World Lives on Less than $5.50 a Day – World Bank, Washington, Oct. 17, 2018, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/10/17/nearly-half-the-world-lives-on-less-than-550-a-day

Photo (top right): courtesy World Bank Photo Collection.