A great IPCC report, another week of talking about climate change, but where’s the policy cohesion?

A great IPCC report, another week of talking about climate change, but where’s the policy cohesion?

Sam Bickersteth of CDKN reports from this month's Chatham House climate change conference, which tackled the tough implications of the IPCC's Special Report on 1.5°C of global warming.

Special Report is a game-changer for our understanding of climate impacts

For those working on climate and development issues the IPCC’s Special Report on 1.5°C of Global Warming should be mandatory reading. That’s the proposition from the head of a leading global environmental organisation at this month's Chatham House conference on climate change, and I would agree. The report has substantially shifted the conversation from whether we can avoid a global average 1.5°C warming above pre-industrial temperature to whether we should exceed 1.5°C and whether a 2°C planet is feasible.

Thanks to the report, this is no longer a conversation focussed only on vulnerable countries and existential threats to low-lying small island states, but instead it has drawn out a range of impacts. These include devastating differences in the impacts on biodiversity between 1.5°C and 2°C of warming: 18% of insect species would be lost at 2°C, as opposed to 6% lost at 1.5°C.

The CDKN blogs published in response to the 1.5°C Report this month indicate the varied impacts of 1.5°C of warming and more, across regions and climate “hotspots”. (In climate hotspots such as Namibia and Botswana, average global warming of 1.5°C translates to 2 and 2.2°C of warming respectively, and a 5 percent reduction in rainfall.)

The IPCC has noted that the opportunities and benefits of limiting warming to 1.5°C are unexpectedly high. For example, the report highlights threats to human health from climate change – simply put, any warming at planetary level is bad for human health and creates costs for health systems. There is very high confidence that if average global warming can be limited to 1.5°C, then fewer heat-related deaths and illness will result. Limiting warming to 1.5°C may also reduce the proportion of world population exposed to climate related water stress by 50%. Foundations (such as the Rockefeller Foundation-based Economic Council on Planetary Health), the World Health Organisation, researchers and others are increasingly supporting knowledge and policy development to address the climate and health nexus.

Adaptation to climate change has been given significant attention throughout the report. But it is also a strong call to accelerated emissions reduction, which will require a massive increase in ambition from the current national climate plans or NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions), which currently add up to a “3 degree” world. Furthermore, the report is a reminder of the need for strong, ongoing collaborative international action. The consensus in the Chatham House meeting was that politics is the biggest obstacle to human behaviour change. Climate change is accelerating just at a time of emerging nationalism and weakening of the multilateral system.

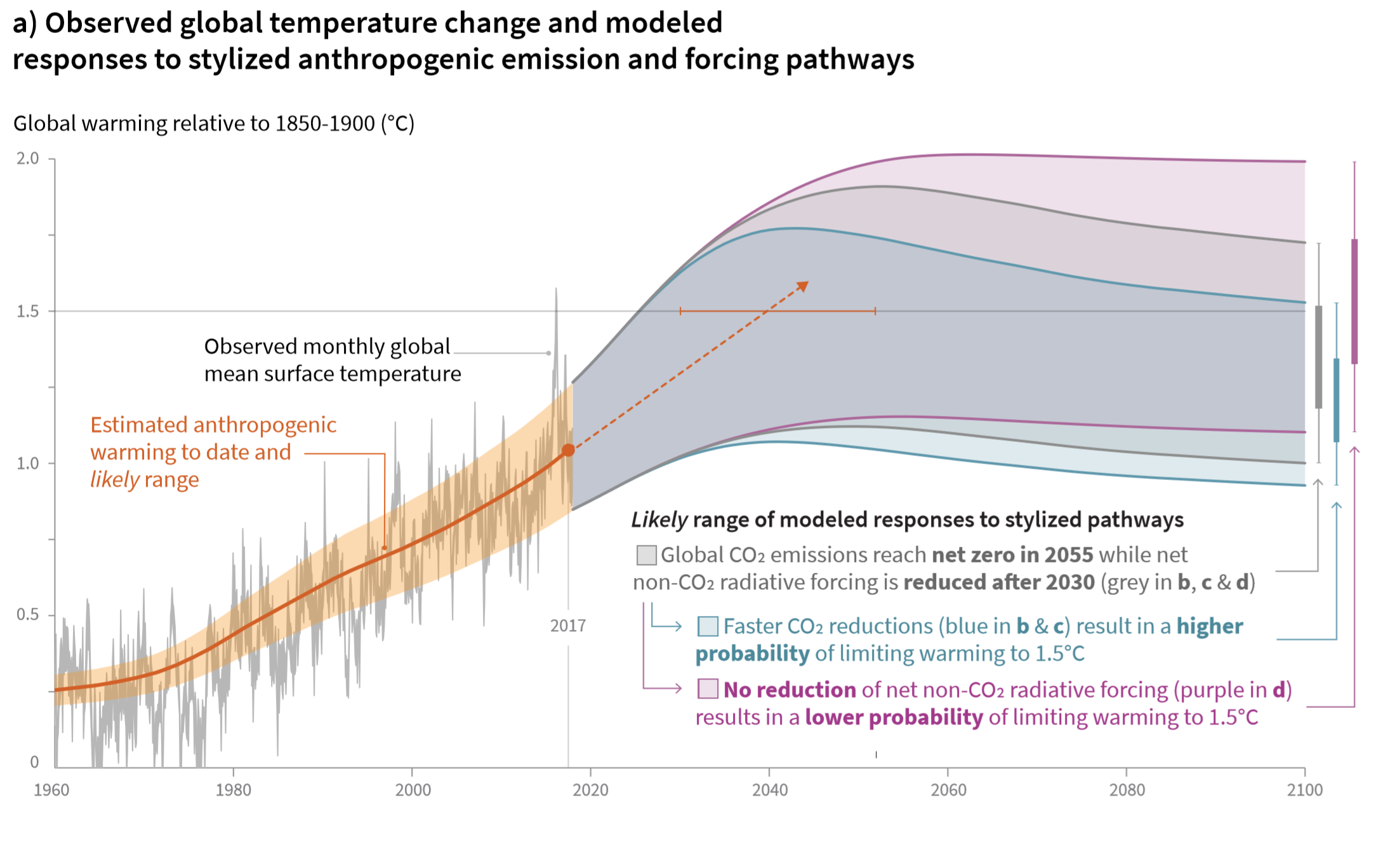

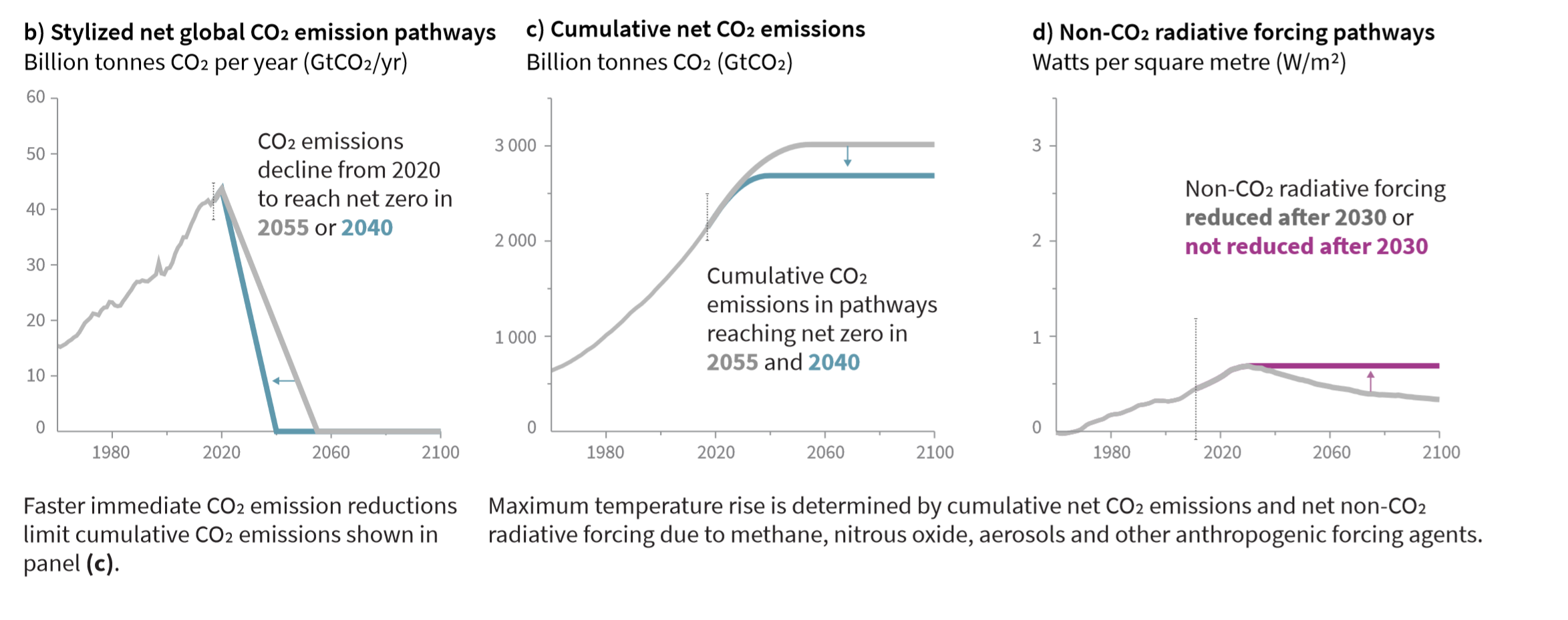

An innovative aspect of this IPCC report is the development of illustrative pathways or system transitions consistent with 1.5°C, all of which are technically feasible (see diagram, below). All show dramatic reductions in emissions needed but pathways consistent with 1.5oC of warming focus attention on the need for cutting not only CO2, but the other greenhouse gases (methane, nitrous oxides, aerosols, etc), fast. This points to the fact that there are some real choices for political leaders to make with respect to our future.

Low carbon growth – success stories

There is undoubtedly a positive story of growth in the low-carbon economy which the UK has feted in its Green Growth Week. It’s a story of fast exit from coal, innovation, investment and industrialisation and scaling up of offshore wind and generation of jobs (already 400,000 green jobs in the UK’s low-carbon economy) in a matter of years. Government ambition for clean energy has led to an effective policy and regulatory framework which in turn has raised business ambition to innovate and reduce costs; this has created a virtuous cycle in which further ambition is raised, subsidies are phased out and new opportunities are developed. The clean energy story is now being played out in transport and the shift to electric vehicles at global scale.

The Chatham House meeting highlighted how China’s centrally planned, hierarchical approach has enabled an impressive reduction of carbon intensity (5% annually) but others called on the need for stronger ‘bottom-up’ movements to mobilise change and raise climate ambition.

‘Turbo charged’ policies needed to advance climate goals

Speakers at the Chatham House conference called for decision-makers to avoid complacency, and for greater policy coherence to progress climate goals. For example, onshore wind is the cheapest form of energy in the UK but its development is effectively blocked by a narrow set of political interests. The UK is still building energy inefficient homes that will need to be retrofitted and the government is reluctant to address issues of diets with high carbon footprints.

UK Minister Claire Perry – speaking on the record – said she would not tell people that they should reduce their meat consumption when a range of nudges, incentives and other regulations could do much adjust food systems towards lower emissions (with better health outcomes) in the manner in which energy systems have already changed. The IPCC’s report sets out the need to address lifestyle and consumption issues, which are politically difficult to address.

Financing the transition to a 2°C- or 1.5°C-consistent world is underway, with encouraging signs of attention by the capital markets that goes beyond the growth of green bonds and integration of climate risk. There are some 42 carbon tax schemes in operation around the world and new guidance on climate related risk disclosure emerged from the Bank of England this week in support. But many banks and pension funds are adjusting just a part of their portfolios and failing to shift the majority of their resources away from fossil fuels and high emitting sectors or factor in adaptation.

Discussions indicate that markets, innovation and technology are moving in the right direction, but the low-carbon transition needs to be ‘turbo charged’ by policy and stronger regulation by governments. We see this emerging in a limited number of countries but much more is needed. Will the findings of the IPCC report and a good outcome from the forthcoming United Nations climate negotiations in Katowice, Poland (COP24) enable the actions to measure up to what climate change is demanding?

Figure: From the Summary for Policy Makers of the IPCC's October 2018 Special Report on 1.5°C of Global Warming: