Challenges of climate change adaptation: Insights from vulnerability assessments of Dhulikhel and Karjanha Municipalities in Nepal

Challenges of climate change adaptation: Insights from vulnerability assessments of Dhulikhel and Karjanha Municipalities in Nepal

The following blog, by Manju Adhikari and Rahul Singh of CDKN Asia, highlights Nepal’s significant vulnerability to climate change.Vulnerability assessments highlight that impact is disproportionately felt by those facing marginalisation. As a result, localised adaptation plans need to address both climate hazards and the needs of marginalised groups.

Nepal is one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world. With frequent exposure to natural hazards, it faces urgent threats to its economy and the wellbeing of its people. Every year, lives are lost and livelihoods are impacted. In September 2024, record-breaking rainfall caused devastating floods and landslides, claiming over 200 lives. Additionally, according to the Asian Development Bank, climate impacts could reduce Nepal’s annual GDP by 2.2% by 2050. These hazards disproportionately affect marginalised communities, placing additional burdens on women, children, and people with disabilities. This is highlighted in the findings of a UN Women report, released at COP28, which predicts that climate change could push around 158 million women into poverty by 2050.

Urban growth meets climate risk

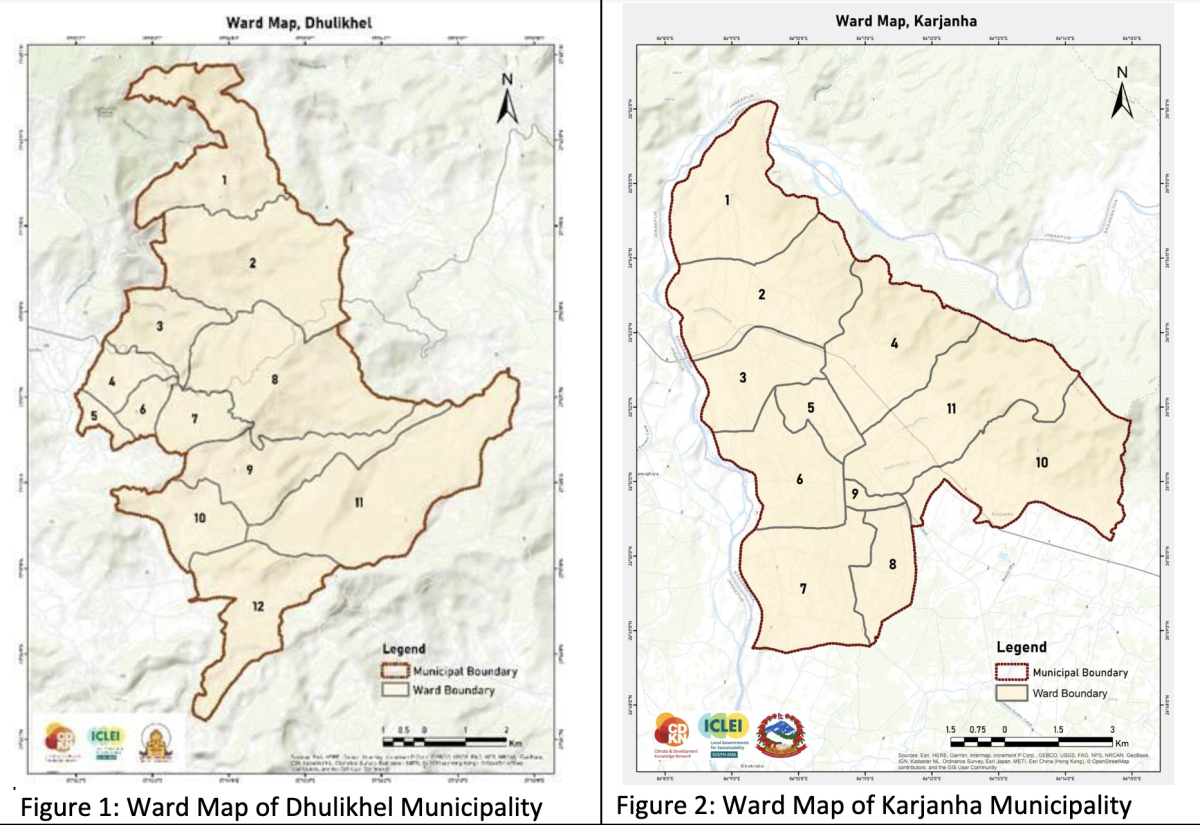

Rapid urbanisation and rising climate risks demand localised adaptation in municipalities. Under its Phase III-Knowledge to Action programme, the Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) is supporting Dhulikhel and Karjanha municipalities in developing inclusive Local Adaptation Plans of Action (LAPAs). The LAPA’s are comprehensive and community-driven plans and are being designed in collaboration with the ICLEI South Asia team to respond to urban expansion and climate risks, aligning with Nepal’s broader commitments under the Nationally Determined Contributions. Of the two regions, Dhulikhel, a hill town in Kavrepalanchok District, is Nepal’s first WHO-recognised healthy city, and is growing as a hub for health, education, and tourism. However, the wellbeing of its people and the stability of its economy is threatened by climate change. Conversely, Karjanha in Siraha District faces several interconnected challenges amid population growth, which are exacerbated by the impact of climate change.

Assessing vulnerability on the ground

As part of the effort to develop LAPA, CDKN Asia conducted a ward-wise Vulnerability Assessment in 2024 in both municipalities. The assessments involved secondary research, focus group discussions, and shared learning dialogues with community members and local stakeholders. These engagements aimed to identify climate risks and vulnerable hotspots, sectoral impacts, key actors, and existing adaptive capacities to ensure inclusive and responsive adaptation plans. Most importantly, they strongly emphasised the voices of women and marginalised groups to ensure the resulting LAPAs are inclusive and effective.

Climate change impact by sector

During the visit, the team observed that both cities are experiencing increasing temperatures and unpredictable monsoons. These climate change impacts are causing prolonged drought, forest fires, flash floods, and landslides. The key findings of the assessments are summarised below:

Agriculture

In both municipalities, agriculture is the backbone of local livelihoods. However, shifting weather patterns and natural hazards are undermining productivity. Dhulikhel, once known for its orange orchards, is now experiencing declining yields and wilting trees. Many farmers have shifted to crops like potatoes and seasonal vegetables, but the transition has reduced both profitability and food diversity. In Karjanha, many women without land, from marginalised communities, depend on adhiya (sharecropping) agreements. However, crop damage from water shortages, pests and wild animals leaves them vulnerable to debt and food insecurity. Limited access to finance and technology traps them in traditional practices that are increasingly ill-suited to a changing climate.

Water

Water scarcity is a growing concern in both municipalities. In Dhulikhel, natural springs are drying up, and the municipal water treatment plants cannot meet the town’s needs. As a result, many households depend on public taps and untreated sources. During the dry season, women in Wards three and five spend hours queuing at standposts, which are connected to a water distribution system, time that could otherwise be spent on income-generating or caregiving activities. In Ward six, some homes go without water for up to a week.

Karjanha faces similar challenges. In many wards, people depend on shared wells, especially those home to marginalised communities. In Ward 10, there is not a single functional well; residents must fetch water from neighbouring areas. The lack of reliable water sources affects irrigation, sanitation, and hygiene – issues that disproportionately affect women, children, and older people.

The monsoon season brings additional risks such as floodwaters that contaminate water sources. This increases the risk of waterborne diseases and other health risks for marginalised groups, especially women, children and older people. The lack of alternative water sources leaves communities vulnerable to prolonged water shortages, which affect farmers, including women farmers, who have limited capacity to adapt due to the lack of resources and relevant information.

Waste management

Inadequate solid and wastewater management compounds climate vulnerability. In both municipalities, the lack of waste segregation at source and irregular waste collection practices lead to open dumping in rivers and fields. Open defecation persists due to inadequate toilet facilities, while the high cost of clearing septic tanks is a financial strain on families. In Karjanha, septic tanks are often emptied into farmlands and fishponds, posing serious health and environmental risks. Again, women, typically responsible for household hygiene, are particularly affected. Inadequate drainage contributes to waterlogging and mosquito breeding, increasing the incidence of dengue and other vector-borne diseases. Without systemic solutions, women remain overburdened and under-supported in their efforts to maintain healthy living environments.

Forests

Forests provide essential ecosystem services in both municipalities, helping regulate rainfall, recharge water sources, and support biodiversity. However, rising temperatures and irregular rainfall patterns are drying forest areas and reducing spring recharge. Invasive plant species like Ageratina Adenophorum (Banmara), along with forest fires and deforestation for firewood and fodder, are weakening forest ecosystems, particularly in the Chure Range near Karjanha.

Women and low-income families, who rely on forests for daily needs, face growing hardships as their access to fuel, fodder, and forest products diminishes. The loss of forest cover also contributes to water scarcity and biodiversity loss, creating a feedback loop that worsens local vulnerabilities.

Who’s most at risk?

The assessments revealed that climate change doesn’t affect everyone equally. Existing inequalities rooted in caste, class, gender, and geography shape the extent of vulnerability. Women, particularly from marginalised castes and economically disadvantaged backgrounds, face the greatest risks due to limited access to resources, land, and decision-making platforms.

CDKN’s assessment evaluated adaptive capacity using three criteria: ability to respond and reorganise after climate hazards; access to finance and technology; and access to information and decision-making. Women consistently scored the lowest across all three criteria.

For example, women farmers without their own land in Karjanha struggle with failed crops due to a lack of savings or insurance. In Dhulikhel, women’s reliance on drying springs and caregiving roles increases exposure to climate-related health risks. Despite their central role in food and water systems, their voices are often excluded from adaptation planning.

Conclusion

The assessments reveal that women and other marginalised groups in both municipalities are highly susceptible to climate risks due to their restricted adaptive capacity. They have limited access to resources, decision-making spaces, and information, despite being on the frontlines of agricultural, water management, and caregiving. Declining crop yields, erratic rainfall, and inadequate access to clean water threaten their livelihoods and heighten climate vulnerability. Building resilience in Dhulikhel and Karjanha must prioritise the needs of these groups by integrating their voices into planning and decision-making. To incorporate identified vulnerabilities, both Dhulikhel and Karjanha Municipalities are ensuring their LAPAs are grounded in inclusive and evidence-based processes.