POLICY BRIEF: How can the Green Climate Fund initiate a paradigm shift?

POLICY BRIEF: How can the Green Climate Fund initiate a paradigm shift?

World leaders and governments paved the way for the establishment of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) through the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) agreements made at the Conference of Parties (COPs) in Copenhagen (2009) and Cancún (2010). The key objectives of the UNFCCC are to limit global warming to below 2°C (or even 1.5°C) and to make societies more resilient to the expected impacts of climate change. ‘Business as usual’ is not an option if we are to achieve this; we need “a global remodelling of economy and society towards sustainability [...] comparable with the two great revolutions which have crucially shaped world history: the Neolithic Revolution (the diffusion of arable farming and animal husbandry) and the Industrial Revolution (the transition from an agrarian to an industrial society)”.This can only be achieved if high-emitting countries, which have the greatest historical responsibility for climate change, meet their responsibilities and decarbonise their economies.

Key messages

- The objective of the Green Climate Fund is to achieve a paradigm shift towards low-carbon and climate-resilient development pathways. This requires ambition, in the design of funded activities and in the provision of financial resources to the GCF.

- A paradigm shift might imply moving to more programmatic approaches, for example approaches covering whole sectors or economies.

- Strong country ownership is essential for a paradigm shift to occur and important for ambition; it will ensure that new ways of working endure in the long term.

- The GCF can create the conditions for achieving a paradigm shift by providing clear incentives and guidance for ambitious proposals by governments and sub-national actors, by developing access modalities that ensure strong country ownership by supporting the necessary capacity development, and by encouraging robust knowledge sharing. This must be matched with the provision of large financial resources to the fund.

Download the policy brief How can the Green Climate Fund initiate a paradigm shift?

Yet the development pathways of developing countries also need to shift. While countries can expect low-carbon development to pay off economically, developing countries will require technological and financial support from developed countries to make this shift.

The GCF can play a central role here by directing financial resources to these countries, generating knowledge and experience, and promoting successful practices. While there is not yet a fixed decision on the GCF’s financial size, it will be a vital instrument for channelling a significant share of the US$100 billion that has been promised annually by developed countries by 2020 for climate action in developing countries.

Additional steps to put the GCF into operation were taken through the approval of its Governing Instrument at COP17 in Durban (in 2011). A key element agreed in Durban was the GCF’s objective to promote, in the context of sustainable development,“the paradigm shift towards low-emissions and climate-resilient development pathways.” This must be seen within the context of the GCF’s other objectives and guiding principles, which include making a significant and ambitious contribution to global efforts towards combating climate change(paragraph 1, Governing Instrument). Other principles that are instrumental towards achieving the GCF’s objectives include that it will “play a key role in channelling new, additional, adequate and predictable financial resources to to developing countries and catalyse climate finance, both public and private, at the international and national levels.” (paragraph 3, Governing Instrument).

These objectives place great expectations and pressure on the GCF. There is a risk that these high expectations will slow down the pace at which the GCF comes into operation. Yet, without this high ambition, there is also a risk that the willingness to provide funding to the GCF might be lower; its ambition is what makes it stand out and will allow it to become the “main global fund for climate change finance.” (paragraph 32, Governing Instrument).

The cornerstone for achieving these ambitions will be set in the governance of the GCF; the type of projects and programmes that it funds will also be of crucial importance. This topic was discussed at the 4th meeting of the GCF Board through controversial and as yet unresolved discussions.

This policy brief provides background information about options for the GCF’s governance structure and potential ways for assisting developing countries in pursuing the paradigm shift.

Aspects of a paradigm shift

Paradigm shift and transformational Change

Terminology matters. During the preparatory phase of the GCF, when the GCF’s Transitional Committee discussed the Governing Instrument, the term ‘transformational change’ was disputed because of its lack of definition and different understandings. To prepare for the Transitional Committee’s final meeting, a workshop was held to discuss what the term meant. The Parties eventually agreed on another term: a ‘paradigm shift’ towards low-emissions and climate-resilient development pathways.

In our view, ‘paradigm shift’ and ‘transformational change’ – both always linked to low-emissions and climate-resilient development – imply a similar level of ambition in the GCF’s objectives and can thus be used interchangeably. However, since ‘paradigm shift’ is the Parties officially agreed to, we will use this term in this policy brief, while recognising that ‘transformational change’ also appears in relevant background papers to the GCF meetings. Farruqh Khan (an alternate member of the GCF Board) and Dustin Schinn recently introduced the concept of a ‘triple transformation’, which addresses “national and international policy; domestic and global resource mobilisation; and access modalities”.

Implications of a paradigm shift

In our view, a paradigm shift means a shift away from practices that are incompatible with the challenges of climate change. In terms of mitigation, this means moving away from fossil fuel-based economies, which implies great changes in our energy, industrial and transport systems in particular. For instance, making a coal power plant more efficient would not, in our view, be a paradigm shift since the basis of the energy system (fossil fuels, centralised) would not change. But a change in the entire power generation and distribution system, towards renewable energies that are more decentralised and locally controlled, would be a paradigm shift. Paradigm shifts can happen at local, sub-national, national and even global levels. Further, they can cover one or several economic sectors, or even a whole local or national economy.

The paradigm shift can be guided by certain objectives (such as envisaged emission reductions) and should build on existing legislative frameworks. However, it cannot just be imposed from the top down. It is often a matter of continuous and dynamic searching and learning processes which need to build on “technological advances, new concepts of welfare, diverse social innovations, and an unprecedented level of international cooperation.” As Stafford-Smith (2010) notes, “functioning at one scale (e.g. farm sector or coastal community) may require transformation at the next scale down (e.g. move farms or shoreline buildings)”. Similarly, it is likely that action on the ground is initially required to prepare for more ambitious policy frameworks. For example, cities often play a key role in catalysing broader climate action.

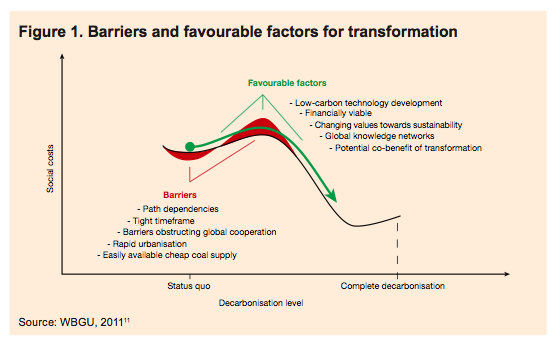

Achieving a paradigm shift might also require the breaking up of established structures and path dependencies (see Figure 1). Changing economic development pathways will incur costs and benefits, as well as bringing new responsibilities for policymakers and societies. For example, these changes might affect actors differently, with some people in a country facing increasing costs while others benefit. Changing pathways may also require financial support to facilitate low-carbon technologies and resources if they are not competitive against existing technologies or resources; for example, an accessible and cheap coal supply could be a barrier (see Figure1). Past experiences support this theory. Since the industrial revolution – a transformational change on the highest level – it has been evident that new technologies are one of the main drivers for transformation. Low-carbon technology development is an example of this; Figure 1 identifies further factors that can drive transformation.

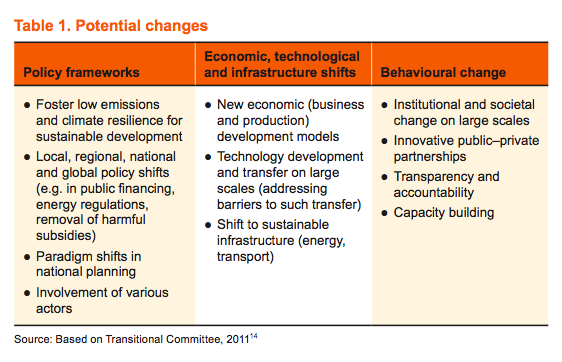

A full paradigm shift needs to be supported by policy frameworks and economic, technological and infra-structural shifts, as well as changes in personal behaviour. Table 1 lists the key approaches with regard to the potential changes needed in these different areas.

GCF modalities to initiate paradigm shifts

GCF funds disbursed to implement projects and programmes should contribute to achieving the GCF’s overarching objectives. One way to allocate funds more explicitly is to break down these objectives into specific result areas.

Result areas

To prepare for the 4th GCF Board meeting, the Interim Secretariat prepared a background paper that presented options for potential priority result areas. The result areas proposed differ strongly between mitigation and adaptation; those for mitigation identified specific sectors that are generally most relevant to the mitigation challenge, and the background paper justifies the sector’s mitigation potential. Those proposed for adaptation include options from selecting specific sectors to capacity-related aspects; there are also proposals for cross-sectoral areas.

However, this differentiation missed some key aspects relevant to a paradigm shift, despite providing interesting food for thought. For example, facilitating capacity for programmatic and transformative activities is crucial for both mitigation and adaptation, not only adaptation. And increasing numbers of developing countries are considering integrated approaches to adaptation and mitigation, while certain long-term infrastructure projects may be relevant to mitigation and adaptation. Also, the background paper does not clearly cover issues such as the integration of mitigation and adaptation into national policies, despite their crucial importance.

The GCF Board could not agree on any of the result areas proposed, however. An important barrier to constructive discussions appeared to be a lack of clarity on the role of these result areas: whether they should prioritise the kinds of activities needed with each result area (thus excluding others initially), which would result in a certain prescription for recipient countries with regard to the sectors covered, or whether they should be used to group proposed activities to facilitate the comparison of proposals and identify suitable indicators. Some board members argued that more time was needed to consider the proposals; some were concerned that a decision on specific results areas – for example ‘Increasing access to transportation with low-carbon fuels’ or ‘Reducing energy use from buildings and appliances’ – might preclude the aspects most relevant to a particular country, for example forestry.

Board members mentioned that the results areas did not focus sufficiently on policy transformation. Another concern was that the recipient country should decide upon the areas in which it needs international support, making it a question of country ownership. As long as the countries provide activities in areas that are relevant from a mitigation and/or adaptation perspective, there is no conflict with the ownership principle.

Board members mentioned that the results areas did not focus sufficiently on policy transformation. Another concern was that the recipient country should decide upon the areas in which it needs international support, making it a question of country ownership. As long as the countries provide activities in areas that are relevant from a mitigation and/or adaptation perspective, there is no conflict with the ownership principle.

Agreeing on some clear priorities for result areas is important, however. The GCF Board should avoid lengthy discussions on creating a ‘perfect list’ and focus on actions. What seems to be most important for achieving the objectives of the GCF is the relevance of the proposed actions to the potential for paradigm shifts. For example, if a country that has its highest shares of emissions in energy and industrial production proposes a programme covering a separate area that is insignificant in terms of national emissions, one could question whether this would meet the GCF’s objectives, even if it would fit into a priority result area.

Yet this should not mean that only mitigation programmes should be financied in high-emissions countries. There are examples of a paradigm shift in smaller countries with lower emissions that have great value for their future low-carbon development and demonstrate good practice. Similarly in adaptation it is difficult to justify why a specific sector should be picked out globally. In some countries, poor people may be most negatively affected by climate change with regard to their food security; in others, water shortage might be the biggest problem.

The ambition in programmes proposed to the GCF can better be assessed from this basis. In order to achieve a paradigm shift, it will often be necessary to move away from a small, project-by-project approach towards more programmatic approaches. The latter could include several small but closely linked projects, which could be interlinked by overall (internal or broader) provisions to allow for easier management and potential adjustments, such as legislation at the national or local level. Table 1 provides a helpful frame for this concept.

A revised version of the result areas has been prepared as an input to the 5th GCF Board meeting. This partially overcomes some of the limitations of the first version. Board members should find a way to move forward on that basis, although further discussions may be necessary on some potentially controversial issues.

Performance indicators

The choice of performance indicators will be important for measuring achievement towards a paradigm shift. The GCF background papers mentioned suggested several potential performance indicators, grouped into two options: ‘project and programme outputs and performance indicators’ and ‘transformative impact of GCF activities performance indicators’.

Again, the role of these indicators needs clarifying. Will they be used to compare programmes with regard to their cost-effectiveness? This may benefits but runs the risk of oversimplified assessments. Or will they be used to measure the performance of projects against their own stated results? This would be reasonable and could be combined with different modalities of results-based finance. Or will they just be used to aggregate results so that the GCF can demonstrate its impact and learn from the results achieved?

This policy brief cannot discuss potential indicators in detail, but it is important to clarify the role of the indicators and their limitations. A common approach for international funds is to identify a set of core indicators that should be used by all projects, wherever applicable, but which should not prevent the use of additional indicators that might be more appropriate. Providing such indicators from the top down can help recipients with the design of their projects, but it should not prevent the identification of suitable indicators from bottom up. The GCF must deliver on climate action in the long term – an objective of the paradigm shift – but must also achieve results immediately, in terms of mitigating emissions and providing adaptation benefits. This is an important challenge to address and the choice of indicators will be influenced by these two timeframes.

Country ownership: an essential prerequisite of ambition

Some of the discussions at recent GCF Board meetings could imply a disconnect, or even a contrast, between country ownership and ambition. There are fears that increased country ownership, for example direct or enhanced direct access to funds through national funding entities, might lead to money not being used for ambitious actions; there are also concerns over the potential misuse of funds. These partially explain the hesitant behaviour of some developed countries towards a stronger focus on direct access and enhanced direct access. However, this argument neglects the important potential of direct access regarding enhanced ownership. At the same time, the call for ambition should not be regarded as contrary to the principle of country ownership; rather, it needs to be defined in the national context but with regard to the GCF’s key objectives.

We believe that achieving a full paradigm shift will not be possible without strong country ownership. Any new approaches and structures must be embedded in the recipient country’s own strategies in order to ensure sustainability. It is the country’s government institutions, private sector, civil society organisations and citizens that will need to continue on the road towards achieving the paradigm shift once GCF funding has ended or is reduced.

An interesting proposal by Khan and Schinn suggests that while each country decides its level of ambition, the instruments and conditions used and funding provided by the GCF will – besides considering the country’s group affiliation (i.e. Least Developed Countries) – be more beneficial to recipient countries with higher ambition. This approach differs according to whether the proposal involves mitigation, adaptation or the private sector.

One challenge that would remain, even with this approach, is how to actually measure ambition and how far a country is moving towards a paradigm shift. These factors will help to decide which instruments and terms for funding should be used. This is closely linked to the choice of performance indicators discussed above. While Khan and Schinn point out that no project would be rejected, this approach would help board members to prioritise among the many projects and programmes seeking support.

Conclusions

The GCF is meant to become the main fund for international climate finance, so in general its support should be available to all developing countries. However, the GCF Board will need some sort of criteria to assess the quality of proposals and whether they support the key objectives of the GCF. Modalities to assess proposals could include the following aspects:

- Funding decisions could be based on the level of ambition shown in actions towards a paradigm shift and the project or programme’s comprehensiveness. An important element is the relevance of a proposed action to the climate-related problems in that country.

- A country’s capacity to implement projects and its needs should both be considered when deciding what constitutes an ambitious proposal; the latter is especially relevant for the most vulnerable countries. This could be combined with a certain floor allocation for the most vulnerable countries, which would ensure a minimum level of funding for them. For example, adaptation finance (and to some extent for mitigation finance) would fund activities meeting certain key requirements, with the ambition element being less relevant to avoid setting benchmarks that might delay action.

- Proposals aiming towards a paradigm shift should include near-term benefits as well as long-term benefits. Another way of ensuring immediate impact could be allocating a certain share of the available funds on a competitive basis, such as the extent of CO2 reductions achieved (but taking into account inter alia the GCF’s safeguard provisions).

- Embedding the funded activity into national strategies and programmes, and incentivising the dynamism of sub-national and local actors, is important for ensuring sustainability after the duration of the GCF-funded project. It also allows lessons learned to be disseminated. Strong stakeholder engagement processes in the identification and implementation of proposals are crucial.

There are several ways to address the concerns that strong ownership might mean lower ambition:

- The GCF could follow the general principle of Khan and Shinn’s approach: that the level of ambition is up to each country, but the more ambitious a country’s proposal is (within its capabilities), the better the funding conditions will be.

- It is important to find mechanisms that ensure the best implementation and use of funds under access modalities with high ownership. This should be supported by accountability mechanisms (including the independent redress mechanism mentioned in paragraph 69 of the Governing Instrument), which include citizen-based accountability.

- Countries should be encouraged to share their experiences in moving towards this paradigm shift. This could be done via an internet-based platform, through joint learning missions or by inviting countries to share experiences from their activities at GCF meetings. This could constitute one of the global knowledge networks identified as a favourable factor for transformational change in Figure 1.

- A provision for evaluation and reporting, and conducting independent analysis of a project, should be in place to check if it is actually progressing towards a paradigm shift. For many countries, given their understanding and capacity, it is hard to comprehend what this change means and what is expected at the end.

A full paradigm shift in many sectors and countries is not achievable with the volumes of finance available from conventional multilateral funds. Significant amounts of financial support will be needed, which could be used to trigger even larger investments. It is therefore important that these contributions are provided as soon as possible, particularly by countries with finance obligations under the UNFCCC. For upcoming GCF Board discussions, all board members should have the objective to find pragmatic ways to move forward and allow proposals to be made as soon as possible. These proposals should be in areas that recipient countries have identified as the most relevant and that meet the objectives of the GCF. Developing frameworks and provisions that harness the potential of increased country ownership for ambitious actions can facilitate the required convergence among board members.

Download the policy brief How can the Green Climate Fund initiate a paradigm shift?