How can we document adaptation for the global stocktake of the Paris Agreement?

How can we document adaptation for the global stocktake of the Paris Agreement?

Countries still need to set the rules for measuring progress on climate adaptation under the Paris Agreement. In anticipation of the critical United Nations climate conference this December in Katowice, Poland, to decide the "Paris rulebook", Katharine Vincent, Emma Tompkins, Robert Nicholls and Natalie Suckall of the Collaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Asia and Africa (CARIAA) programme suggest a way for governments to move forward.

The signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015 signalled a positive step forward in addressing climate change. As well as aiming to limit global temperature increase to below 2 degrees Celsius, with a view to limiting it to 1.5C, the Paris Agreement calls for stronger commitments to adaptation. It puts in place transparent mechanisms to ensure progress towards these commitments. A key component of this transparency mechanism is the global stocktake – a five yearly review of collective progress on both mitigation and adaptation.

[Ed: the first global stocktake of progress on the Paris Agreement will be in 2023 - this CDKN graphic timeline shows how the process will unfold.]

The global stocktake has several purposes. It will be a mechanism to recognise the efforts of developing country parties – tracking progress against adaptation commitments and intentions outlined in Nationally Determined Contributions and National Adaptation Plans. It will also enable Parties to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of adaptation action, thereby enabling the ambition commitment – a unique element of the Paris Agreement that enables strengthening of mitigation and adaptation commitments over time.

In the years since 2015, the various bodies within the UNFCCC have been focusing on the process of developing rules, procedures and mechanisms to implement the Paris Agreement : known as the “Paris rulebook”. The rulebook is due to be completed by the next Conference of the Parties in December 2018, but progress has been slow. Bringing together 1,600 people during September’s impromptu Bangkok Climate Change Conference was hastily planned after the last inter-sessional in May failed to make the necessary progress.

One of the many sticking points has been the sources of information and modalities for the global stocktake. There is no one universal definition of adaptation, and conceptual agreement is impeded by many normative assumptions about what adaptation achieves (e.g. that it should generate positive benefits for all) and how it is different from development. Without agreement on what adaptation is, it is very difficult to know how to measure it or determine its effectiveness.

The discussions on defining adaptation have continued for decades. However, with near universal agreement that adaptation is necessary (as committed to by governments in the Paris Agreement), the lack of conceptual clarity can no longer impede the creation of a baseline of adaptation, as required in the global stocktake.

In a paper recently published in WIREs Climate Change, we outline a way forward on "Documenting the state of adaptation for the global stocktake of the Paris Agreement". The paper proposes a stocktaking approach to document the spectrum and prevalence of adaptation over large scales. The stocktaking approach is based on a method used to develop inventories of adaptation in four deltas within the Deltas, Vulnerability and Climate Change: Migration and Adaptation (DECCMA) project.

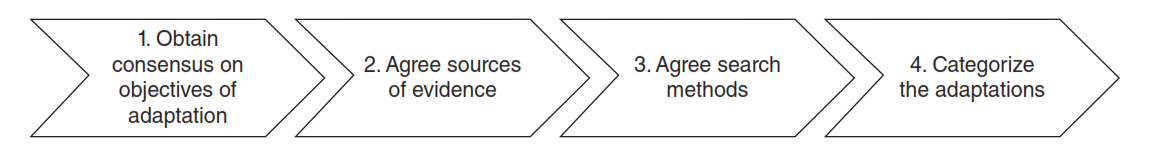

The stocktaking approach involves four steps: (a) obtaining consensus on the objectives of adaptation; (b) agreeing the sources of evidence; (c) agreeing the search method; and (d) categorizing the adaptations (figure 1). With this structure, it should be possible for scientists and policy makers to start to accumulate the evidence of adaptation to create a baseline assessment of what is occurring.

Figure 1: The four step process to document the state of adaptation

The first step avoids many of the heuristic traps by seeking consensus on the broadly agreed objectives of adaptation to multiple stressors: (a) to reduce socioeconomic vulnerability, (b) to address disaster risk, and (c) to support social-ecological resilience.

Once this is completed, the second step involves defining the sources of information that should be searched. We propose that all secondary sources of information (online, offline, journal articles, technical reports etc.) are searched to deliver a complete baseline assessment of adaptation. The success of the search comes from triangulating sources to reduce the risks of misrepresentation and double-counting.

There are various methods for the third step search, all of which are currently used in the sphere of adaptation. These include systematic review, submission of evidence or the inventory approach. Whilst all have strengths and weaknesses, a combination of the systematic review and inventory approach together can include a wide variety of literature, be applied by non-experts, and be cross-checked to avoid double-counting. Effectively documenting the search enables replication and updating in subsequent years.

The fourth step of categorising the adaptations can be done by the objectives as outlined in step 1. Figure 2 outlines various elements of vulnerability reduction, disaster risk reduction and social-ecological resilience, building on insights from the sustainable livelihoods framework, disaster studies, and ecosystem services.

Figure 2: Dimensions of adaptation action

With the Paris rulebook required by COP24 in Katowice in December 2018, including procedures for the global stocktake under the Paris Agreement, continued debates about the definition of adaptation can no longer hamper progress on documenting adaptation. Moving beyond definitional arguments, and using widely agreed objectives of adaptation, our proposed approach is transparent and comparable. With a baseline assessment of adaptation that can be replicated easily over time to monitor progress, it will be more straightforward to assess whether we are improving in our adaptation skills or not, and whether sufficient people are adapting. The gaps highlighted by this documentation will also show us where and how adaptation finance should be spent to effectively reduce adverse effects of climate change.

Contributors to this blog were: Katharine Vincent (Kulima Integrated Development Solutions), Emma L. Tompkins, Robert Nicholls and Natalie Suckall (all University of Southampton)

CDKN occasionally invites guest bloggers to contribute to www.cdkn.org The views expressed are not necessarily those of CDKN or its alliance organisations.

Image: accessing clean water in Pakistan, courtesy DFID.