How to win the argument on climate change

How to win the argument on climate change

I’ve been worrying about how to win the argument on climate change. When (perhaps if . . .) I become Prime Minister, this is my five step plan:

- Find a simple way to tell the story;

- Create a positive message on the transformational benefits of taking action;

- Craft a policy package which aids transition and helps losers;

- Build a leadership group which will deliver long-term consensus; and

- Focus relentlessly on implementation

There’s too much material here for one piece, so this is Part One. More to follow.

Why do I need a plan? Because tackling climate change is tough. It often feels like we take two steps forward and one step back. Every now and again a tragic event like Typhoon Haiyan dominates the news bulletins and people make a link between climate change and the frequency or severity of natural disasters. But then we are back to normal, arguing about who will do what, and about the fine detail of taxes, subsidies or regulations.

That is not surprising. All policies have winners and losers. Ask German industry, worried about high energy prices caused by ‘energiewende’, the transition to renewables. Or Australian electors, apparently so opposed to a carbon tax that they voted out the Government of Kevin Rudd. Or talk to citizens in the UK, campaigning vehemently against windfarms, gas fracking, or a rise in energy prices. Of course, in the long term, everyone wins if climate change can be avoided. In the short term, however, the number and geographical distribution of potential losers makes policy design exceptionally tricky. I remember once being at a dinner with a UK climate change minister, who said quite openly ‘you have to understand that for every company lobbying for more support to renewables, there are three standing outside my door lobbying for less’. And do you know what? Ministers are right to worry about the future of jobs in depressed parts of the country, where many of the current jobs are in power-hungry heavy industry .

So, what to do? I’ve just come back from Colombia, so some examples below come from there.

Find a simple way to tell the story

First, the science is unambiguous that human-induced climate change is real - but the science is far from straightforward. Frankly, I’ve read the latest ‘Summary for Policy-Makers’ from the IPCC, the headlines are clear enough, but it is hard going. You (well perhaps you don’t, but I do) need help to understand such things as Radioactive Forcing and Representative Concentration Pathways. There is a good explanation of RCPs here, they turn out to be different and unrelated models, rather than linked scenarios. That’s quite important if you are trying to read the report.

Also, the aggregate numbers are hard to comprehend.

For example, I understand the point that CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere have reached 400 parts per million, and that that is 40% higher than pre-industrial levels – but then, I think, hang on, that means CO2 has increased by about 100 parts per million, which is equivalent to one part in every 10,000. That doesn’t seem very much. Imagine 50 one-litre bottles of water and you add one teaspoon of CO2, and it makes all that difference? And adding one more would end the world as we know it? I suppose so.

Or take another example. Current emissions are getting on for 50 Gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent a year (see the UNEP Bridging the Gap Report). That sounds like a lot, and it is. But how much is a gigatonne, actually? I read somewhere that one gigatonne is enough to fill the Black Sea, but that doesn’t help, unless you can visualise the area and depth of the Black Sea.

So, public messaging needs simple examples which mean something to people. Sometimes numbers are best, sometimes stories, sometimes pictures. That’s why, as I have argued before, we need to understand the Myers-Briggs profile of the audience: see my thoughts on disrupting the psychological status quo. Also, as I learned from Jonathan Haidt, different people respond to different triggers – empathy, duty etc . . ., so the message needs to be crafted accordingly.

Here’s what I do:

First, as noted, keep it simple, by rounding-up, rounding-down, and avoiding ranges and probabilities. For example, on gigatonnes, it is important to know that we have a total global budget for all time of about 1000Gt of CO2 and that we have already used half of it. So, at current rates of use we only have enough left for 20 years – and emissions are still rising. That’s helpful.

Second, use high-level ‘killer facts’ – like the global carbon budget. I find the cost of disasters to be powerful: the Pakistan floods in 2010 cost 8% of GDP, Superstorm Sandy over $US75bn.

Third, some good images. For example:

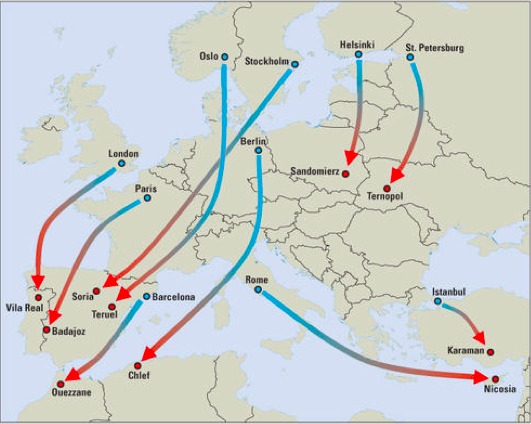

- A sobering map in the World Bank’s World Development Report on climate change from 2010, which shows which places European capitals are likely to resemble by about 2050. As you can see (or find the original here), Oslo and Stockholm are relocated, so to speak, to Northern Spain, London to Northern Portugal, and Berlin to Chlef in Algeria. Try googling some images of Chlef . . .

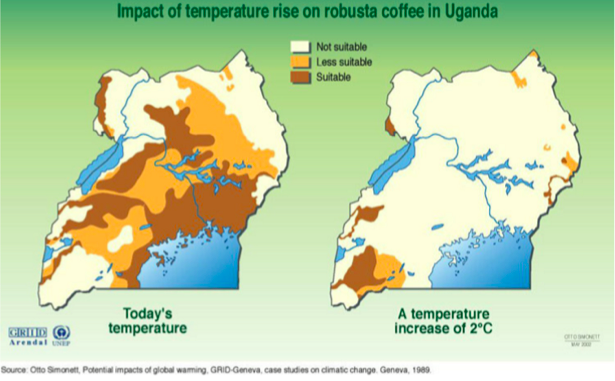

- Another sobering map, this time showing the area suitable for robusta coffee in Uganda, now and if temperature rises by 20 C. This is from the Uganda National Climate Change Adaptation Plan of 2007, and shows coffee almost disappearing from Uganda unless new technology can be found. Coffee, remember, employs 3.5m people in Uganda, and provides 30% of export earnings. There are many similar examples – tea in Kenya, for example, or coffee in Colombia. In Colombia, coffee will move up the mountain by 400m, a very significant change. If there is a mountain up which to move.

Fourth, make it personal. The previous examples relate to impacts. How about emissions? I’ve tried various ways of visualising gigatonnes, but in the end come back to current and future emissions at a personal level. Overall, we seem to be emitting about 7 tonnes per capita on average at present, from all sources, of course much more in rich countries and much less in the poorest. By 2050, that figure will have to come right down, to perhaps no more than 2 tonnes (a figure endorsed by the UK Climate Change Committee, but which may well be on the generous side if mitigation efforts do not pick up speed).

In order to see what that means, it’s good to encourage people to complete a personal carbon calculator, of the kind that is found for most developed countries, though probably not for most poor ones. For the UK, a calculator is here. Colombia has a calculator, here. How many developing countries have personal calculators, I wonder? Has anyone done a register?

Two tonnes, of course, is not much in a modern economy. Most of us working on climate change emit more rather than less than the national average for our country, especially if we fly for work. For anyone living in Colombia, 2t is enough to fly to Beijing, but not fly home.

As an alternative, here is an example I used in Colombia. The country already emits 1.6t per capita and is growing at 4% a year, which means the economy is doubling every 18 years. At that rate, GDP will go up by four times by 2050, as it needs to if poverty is to be tackled. But Colombia will only be able to use 25% more Co2 per capita. In Colombia, by the way, and this is not unrelated, the most dynamic sectors are petrochemicals and coal, which together account for over half of exports. Of course, the emissions are counted at the point of use, rather than the point of extraction, so do not appear on Colombia’s carbon budget.

Fifth, make an emotional connection. Ideally, people need to experience the reality of climate change on the ground, but failing that, television can help. Images from disasters like Haiyan move people. Or a great communicator can touch people’s hearts. I remember once being in Davos and hearing Bill Clinton tell a story about the tsunami. When he paused, you could hear a pin drop. I have repeated the story, of course citing the source, and had a similar impact. Clinton has used the story elsewhere, and here it is, taken from a speech he made to a meeting on disaster prevention and preparedness’:

‘I'd like to close with just a story to remind you of what this is all about. The last time I went to Aceh, I went to one of the camps for the internally displaced where there were thousands of people living. All these little communities, these little makeshift communities elect a community leader to represent them while they are there. I had at my side a young Indonesian woman who had been a television reporter. She quit her job to be an interpreter and to work with people in the camps until the reconstruction was done. So we walked into the camp and I was greeted by the elected leader of the community, a fellow just like everybody else living in the camp, and his wife and his son. This little boy of theirs, nine years old, was the most beautiful child I have ever seen. It was shocking; I could hardly get my breath when I looked at him: luminous eyes, bright smile. So I said to my young interpreter: I believe that's the best-looking boy I ever saw in my life. She said: “Yes, he is a beautiful boy. And before the tsunami, he had nine brothers and sisters. Now they are all gone.’

Finally, but we will come to that in the next piece, leave people feeling empowered not powerless, with an optimistic message that something can be done. As Anthony Giddens observed in his book on the politics of climate change, Martin Luther King did not stir his audience in 1963 by declaiming ‘I have a nightmare’ . . .

Read Part Two, Read Part Three.