Integrating Indigenous knowledge into environmental policies for sustainable forest management in Benin

Integrating Indigenous knowledge into environmental policies for sustainable forest management in Benin

This blog, written by Ferdinand Ayimasse, Esdras Obossou and Edmond Totin, highlights SURVIE NGO’s collaborative project in southern Benin, where Indigenous knowledge from sacred forest traditions is being integrated into national biodiversity policy through multi‑stakeholder co‑production dialogues. By engaging traditional leaders, government bodies, NGOs, and local communities, the initiative aims to bridge cultural and institutional gaps, advocating for legal frameworks, public awareness, and co-governance models to sustainably protect forests and cultural heritage.

Context

The recognition of Indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) in biodiversity conservation is increasing within global science-policy arenas, as reflected in the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) report and the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. In Benin, like in many other African countries, sacred forests serve as hotspots for biodiversity conservation and are generally maintained by indigenous knowledge and belief systems. However, the emerging pressures from land conversion for agricultural purposes, urban planning infrastructure, economic development, and climate stress threaten the preservation of sacred forests and the related cultural ecosystem services. Changes in societal structures, religious values, and belief systems, such as the replacement of tribal religions with Christianity also pose another structural challenge to the conservation of forests. In response to these combined challenges, the local NGO, SURVIE de la Mère et de l'Enfant, in partnership with the Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN), is driving a Knowledge-to-Action (K2A) project, Valuing biodiversity through traditional African knowledge in Central Benin. The project engages diverse stakeholders in dialogues to integrate Indigenous knowledge into national biodiversity policies, promoting inclusive ecosystem management.

This blog aims to showcase NGO SURVIE’s strategy for fostering multi-stakeholder dialogue towards integrating conventional and indigenous forest conservation approaches in the project area.

Stakeholder mapping and engagement

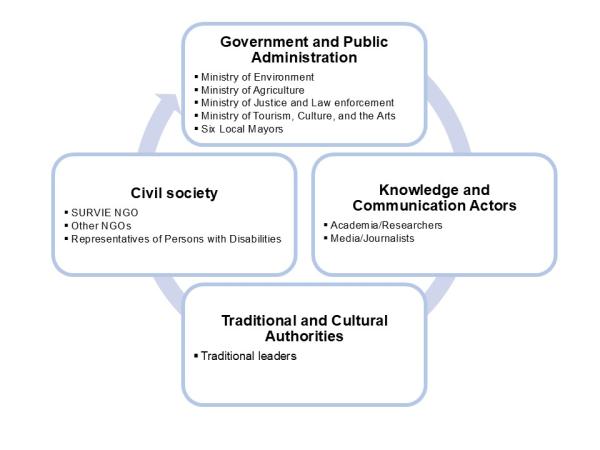

SURVIE NGO recognises that a co-design process, engaging with a diverse range of stakeholders, including policymakers, researchers, and community organisations and their associated knowledge and values, is essential for stimulating effective forest biodiversity conservation. The first co-production dialogue brought together Indigenous communities in the project area to seek their consent for institutionalising their traditional practices associated with sacred forest conservation. Seeking consent is critical because not all Indigenous knowledge can be shared with those without a traditional background. Consent is also important to ensure that traditional knowledge is respected and used wisely. The second dialogue involved a diverse range of national stakeholders (Figure 1), including policymakers, traditional leaders, and natural resource practitioners (NGOs), to co-develop a pathway for effective knowledge co-production to enable forest biodiversity conservation and sustainable management that bridges governance scales.

The six mayors from the project implementation sites were also invited to discuss challenges related to forest management and local governance. The Ministries of Tourism, Justice and Law Enforcement, and Agriculture were engaged to reflect on possible synergies and trade-offs for mainstreaming indigenous knowledge in natural resource conservation. Traditional leaders were involved in explaining the role of cultural heritage in forest conservation.

Framing of the dialogues

At the opening of the second knowledge co-production dialogue, the SURVIE lead gave an introductory presentation to acknowledge the important roles of Indigenous communities as custodians of biodiversity conservation and cultural heritage. Participants also discussed the co-benefits of incorporating Indigenous knowledge into forest conservation policy. "Sacred forests are homes for spirits, which help overcome illness and achieve professional and personal success. Losing these sacred spaces would profoundly affect the social fabric of local communities".

A second intervention focused on the current state of forest conservation in Benin, highlighting the limitations of conventional top-down approaches in natural resource management. Benin has experienced a significant decrease in forest area. Between 2001 and 2023, forest losses were estimated at 46.6 kha of tree cover. Urbanisation and land expansion for agricultural production, such as soya beans, cotton, and cashew nuts, have led to a decline in forested areas. Most farmers prioritise land expansion when they cannot afford fertiliser. A forest officer attending the dialogue session explained that: "Forest conservation is no longer solely the responsibility of forest administration. It should involve local leaders, Indigenous knowledge holders, Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), etc."

Relevance for mainstreaming Indigenous knowledge

Participants highlighted that Indigenous knowledge provides valuable insights into sustainable forest management: “For generations, local communities have developed knowledge on forest conservation, resource rotation, and customary enforcement mechanisms. These approaches are relevant, particularly in the context where conventional conservation methods have failed in enabling the effective conservation of natural resources”. When this knowledge source is overlooked in development plans, the related infrastructure may fail, as illustrated by the following story reported by Mednick, a Canadian journalist: “In Ouidah, Benin's epicenter of Voodoo, a gas station that replaced the Avelekete forest years ago has not turned a profit, residents say. Station employees said that when they filled cars with gas, it turned to water.” This illustrates the influence of local perceptions surrounding taboos related to the destruction of sacred sites.

Forest administration delegates indicated that valuing and institutionalising Indigenous knowledge would enhance community ownership of conservation initiatives and promote long-term engagement and sustainable forest management. As one participant noted, “Traditional practices have helped sustain our forests for centuries. If we neglect them, we can lose not only our biodiversity, but also our cultural heritage.”

Gaps to be addressed by Indigenous approaches

Participants pointed out several gaps in the existing national resource conservation framework that could be addressed by incorporating Indigenous knowledge into natural resource management policy. Some gaps relate to the limited involvement of traditional authorities: “Many local leaders and custodians of sacred forests are not formally recognised in forest governance structures, despite their role in protecting biodiversity.” Others relate to the ineffectiveness of legal sanctions: “While existing laws prescribe penalties for illegal forest exploitation, they remain weak. An individual must be caught in the act of committing the infraction before any sanctions can be applied. Traditional spiritual and customary sanctions, however, have historically discouraged illegal activities by regulating behaviour at the intrapersonal level, and could thus complement legal measures.”

Participants also raised the lack of public awareness: “[...] local communities (mostly illiterate) are unaware of forest protection laws. The legal texts do not always reflect the realities on the ground. Traditional rules are respected because they reflect social and spiritual values.” This highlights the potential role of SURVIE as a knowledge broker in disseminating information about current forest protection policies within local communities.

Way forward

To effectively integrate Indigenous knowledge into formal conservation strategies, participants strongly advocated for a national inventory of traditional conservation practices as a next step, to ensure their inclusion in natural resource conservation policies: “We must establish a legal framework that formally recognises the role of traditional leaders, sacred forest custodians, and Indigenous practitioners in conservation governance.”

Participants also suggested strengthening multistakeholder collaboration: “Strengthening partnerships between Indigenous peoples, government agencies, civil society organisations, and academic institutions will help create a co-governance model of sacred forests that reflects both conventional and indigenous perspectives”. The forest administration is already considering this multilateral collaboration as a result of SURVIE NGO’s advocacy: "We are working to put in place a protocol for co-managing sacred forests in close collaboration with local communities. Forest administration has inventoried so far about a hundred sacred and community forests in the project districts. This is an advantage of multi-stakeholder collaboration”

Integrating co-produced knowledge into national biodiversity policies is crucial for the sustainable management of natural resources. While knowledge co-production offers opportunities to learn across boundaries, it also requires commitment from stakeholders and flexibility in process planning.