From flood maps to mind maps: Participatory systems modelling of floods in Limbe, Cameroon

From flood maps to mind maps: Participatory systems modelling of floods in Limbe, Cameroon

In Limbe, Cameroon, flooding is not just caused by heavy rainfall. Rather from a complex interplay of land-use decisions, poor waste management, weak governance and a lack of infrastructure, with cascading impacts on education, transportation, health, and the economy. Tackling this requires a systems‑thinking approach. The following blog by Dr Lum Sonita Awah, a postdoctoral Fellow at the University of the Free State and an early career research fellow with CDKN, shares how participatory systems modelling can be used to create holistic approaches to flood mitigation and management.

As a disaster risk researcher, the last five years have been dedicated to understanding how African cities like Limbe, Cameroon, are continually overwhelmed by flooding. What I have discovered is illuminating. Floods are not merely the result of heavy rain. They stem from a complex web of interconnected factors, including land use decisions, inadequate waste management, weak environmental policies, infrastructure deficiencies, and human behaviours.

Limbe is a low-lying coastal city that faces more frequent and severe flooding each year. Many of these floods go unreported, and their consequences extend far beyond what is immediately visible. Schools close, businesses suffer financial losses, roads and bridges collapse, families are forced to relocate, and health crises arise. Traditional solutions focus on water management, such as improving drainage systems, building floodwalls, and enhancing emergency responses, however, alone these approaches are insufficient. To sustainably tackle flooding, we must understand the entire system at play, not just the symptoms, but the root causes.

What is systems thinking, and why does it matter?

Systems thinking offers a framework for addressing complex problems by examining the relationships and feedback loops that exist between different components of society, nature, and policy. In Limbe, I utilised a method called Participatory Systems Dynamics Modelling, which involved engaging local stakeholders, including government officials, community leaders, youth groups, and business owners, to collaboratively map out the factors contributing to flood risk.

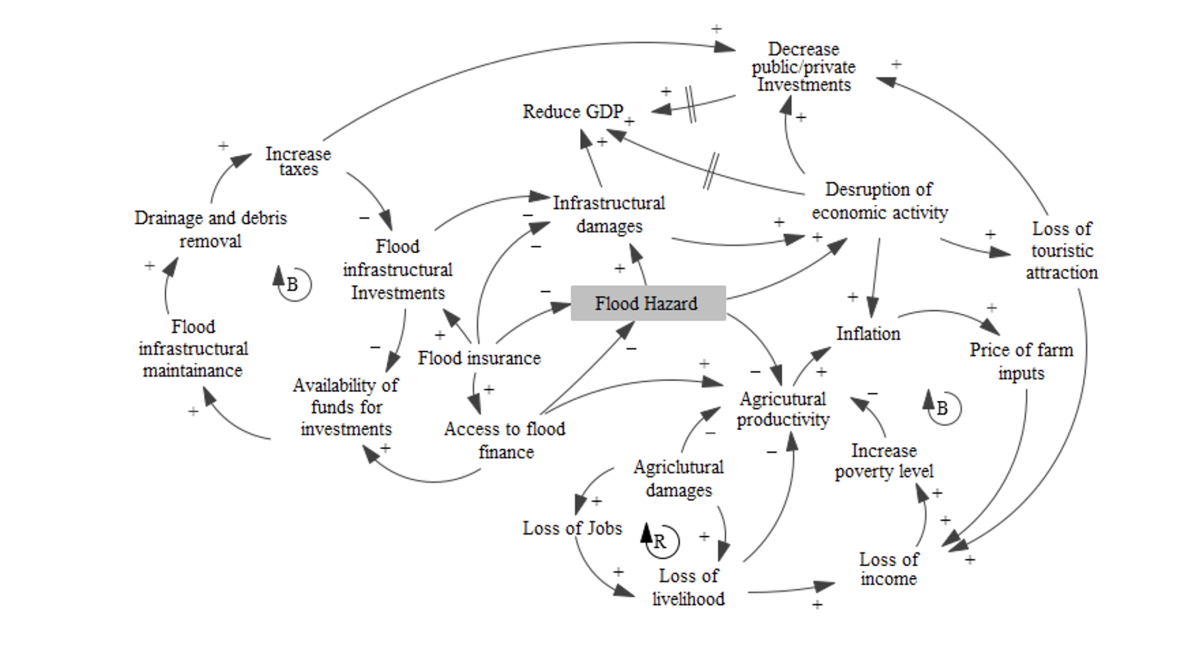

Visual diagrams were constructed to illustrate how issues like illegal construction, clogged drains, deforestation, and lax enforcement of building codes create a chain reaction of consequences. For instance, when drains are blocked, flooding occurs → flooding disrupts transportation → disrupted transportation hampers business → economic losses lead to less investment in infrastructure → and the cycle continues.

To develop these diagrams, we used a co-creation approach where participants first mapped individual challenges using paper stickers, then collectively linked them to their direct and indirect impacts through facilitated discussions. This paper-based output was then digitalised in Vensim, a simulation technology. The digitalised output was presented again to the stakeholders and was validated by the group to ensure accuracy and completeness. This hands-on process helped participants grasp the broader picture, shifting the dialogue from blame to collaboration and moving beyond isolated fixes toward sustainable, multi-faceted solutions. An example of the cascading effects of flooding is shown in the figure below:

Economic Sub-model of Cascading Effects of Flooding in Limbe

The power of participation

One of the most impactful aspects of this work is the emphasis on community participation. Instead of imposing external models, we work together with those who are directly affected by floods. Community members share their lived experiences, what they observe before and after a flood, how they cope, and the support they need. Their insights are invaluable and complement any data set. During our workshops, a market vendor connected drainage problems in the city centre to deforestation upstream. A youth leader noted that plastic waste frequently clogs waterways. A local official recognised that outdated policies have failed to keep pace with the city’s rapid growth. This collaborative understanding fosters trust and lays a solid foundation for effective action.

What can we do differently?

Through our systems modelling in Limbe, we identified four critical areas that influence flood risk:

-

Policy and governance: Weak enforcement of land-use regulations and fragmented decision-making.

-

Environmental degradation: Deforestation, erosion, and unregulated construction practices.

-

Economic strain: Lost income, damaged property, diminished investment in infrastructure.

-

Social impacts: public health challenges, disruption in education, and rising inequality.

Why this matters for Africa

Limbe is not an isolated case. Cities throughout Africa, from Accra to Dar es Salaam to Lagos, face similar systemic challenges. As climate change accelerates, these challenges will only intensify. With the right tools and a comprehensive approach, we can make meaningful progress. Systems thinking enables us to transition from merely addressing symptoms to understanding and tackling the underlying causes. It helps us design solutions that are targeted, inclusive, and sustainable. Additionally, when communities are actively involved in the process, the resulting solutions gain trust. Africa requires more than just increased funding or improved infrastructure; it needs innovative ways of thinking about risk that take into account our unique social, environmental, and political contexts.

Looking ahead

If we are to build flood-resilient cities in Africa, we must shift our perspective from viewing floods in isolation. We must take a holistic view, consider the entire system and create solutions from the ground up. By embracing a systems thinking approach, we can better safeguard our communities and foster a sustainable future for all.