Could $30 oil derail the low carbon transition?

Could $30 oil derail the low carbon transition?

PwC's John Hawksworth and Jonathan Grant reflect on how low oil and gas prices could result in a silver lining for the climate.

Oil prices have fallen by more than two-thirds since mid-2014 with renewed weakness and volatility in early 2016. Over the same period natural gas prices in the US fell by nearly half on the Henry Hub index, while international steam coal prices delivered to the North West Europe hub fell by around 35 per cent.

These sharp falls in prices are good news for fossil fuel consumers/importers and bad news for fossil fuel producers/exporters, but will be there be a price to pay for the climate if low prices boost consumption of fossil fuels, and so carbon emissions? And could cheaper gas and coal undermine the economic case for investment in low carbon alternatives like nuclear, wind and solar power?

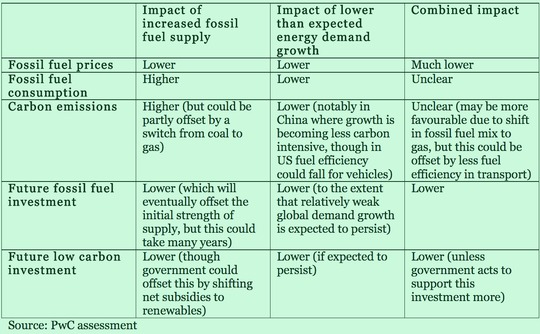

There are a complex mix of potentially offsetting effects here, so it is useful to analyse these using a standard economic framework that distinguishes the effects on fossil fuel prices of:

- increased supply (e.g. shale oil and gas, lifting of Iranian sanctions, lack of OPEC production cuts); and

- lower than expected energy demand growth (e.g. due to the economic slowdown and rebalancing in China and generally muted global economic growth in recent years).

Both of these factors have been at play in recent years, as we havediscussed in previous analysis, but the table below looks at each separately before summarising their combined impact on key variables of interest.

The first key point here is that both these effects tend to reduce fossil fuel prices - leading to the sharp falls we have seen since mid-2014 - but the impact on fossil fuel consumption is unclear as they operate in opposite directions.

Furthermore, since gas prices have on average fallen more than coal prices, there may be some net substitution from coal to gas in electricity generation in particular, which will tend to reduce carbon emissions. On the other hand, oil is less easy to substitute away from at present and is likely to remain the dominant transport sector fuel for many years. So the incentive for people to drive less in more fuel-efficient vehicles will be reduced with cheaper petrol, leading to higher carbon emissions.

So the jury is out on whether the shorter term impact will be higher or lower carbon emissions. Ultimately, however, what matters more for climate change is the impact on longer term energy investment. For fossil fuels, there is clearly less incentive to invest in developing new supplies, and that is already becoming evident in cut-backs by major oil and gas companies in response to the prospect of 'lower for longer' prices. This could eventually push fossil fuel prices back up again by offsetting the recent supply glut, but this could take many years to come through in full.

For low carbon investment, the picture is more complex because it depends a lot on how governments react to lower fossil fuel prices. If they do nothing, then demand for renewables will also tend to come down and this will make investment in renewables less profitable. On the other hand, if governments respond by reducing fossil fuel subsidies (particularly in emerging economies where these are often significant) or imposing higher energy or carbon taxes, and using some or all of this net revenue gain to support low carbon investment, then any adverse impact on this from lower fossil fuel prices could be offset.

For the moment, investment in 'clean energy' seems to have held up well, with Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimating that this rose to a new record high of $329bn globally in 2015, up four per cent on 2014 levels. This reflects the increased momentum towards a low carbon economy in the run up to the Paris climate summit, improving economics, and concerns about air quality in emerging economies like China and India. And there have also been rapid technological advances in renewables since early 2004 when the oil price was last at today's level which have reduced costs of both wind and solar power. Combining this innovation with very low interest rates, means the economics of renewables now hold up better against fossil fuels than they did 12 years ago.

China's national climate plan includes the ambition to install over 100GW of wind capacity by 2020 - not far off the current onshore capacity in Europe - and 70GW of solar capacity. The increase in renewables investment in China may not be affected by low fossil fuel prices as much as in OECD countries, as there are strong social and political forces driving it. And innovation in China as a result of this scale of deployment and the 'learning by doing' might be expected to ripple round the global renewables market.

But there is no room for complacency here, since a prolonged period of low fossil fuel prices could sap the appetite of investors for renewables, particularly if governments reduce subsidy levels in those areas, as we have seen recently in the UK. Increasing biofuel investment looks particularly challenging, given the concerns about potential indirect impacts of conventional biofuel production and the high costs of second generation biofuels. And with low prices at the pump, some drivers may be less inclined to switch to electric vehicles. But if governments instead respond by taking action to price carbon more fully, which may be more politically feasible with oil and gas prices so low, then there could yet be a silver lining for the climate from cheaper fossil fuels.

John Hawksworth is PwC's chief economist and Jonathan Grant is PwC's director of climate change. This article first appeared on Business Green here.