Advice for negotiators at COP21 - Get it done and let's get back to work

Advice for negotiators at COP21 - Get it done and let's get back to work

CDKN's Executive Chair Simon Maxwell provides his outlook for the next week of the UN climate talks at COP21 in Paris. This article was first published on Devex on 30 November 2015.

There are four possible outcomes of the Paris climate change conference, which began on Nov. 30. One is irrationally optimistic; one is too pessimistic. The difference between the other two is small at this stage. My advice to negotiators, therefore, is this: Get it done, celebrate success, and let’s get back to work. How about finishing early, for a change, rather than keeping everyone on tenterhooks into the middle of the night?

Worst-case outcome

The worst-case outcome is not going to happen. This will be no Copenhagen. There is too much momentum behind the talks, and too much political capital invested. There will definitely be an agreement by the end of the talks. That this should be so is a success for Christiana Figueres, the executive secretary of the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, for the Peruvian and French Committee of the Parties presidents, as well as all those who have worked hard to make the case and secure support.

Negotiators have played their part too, with an impressive range of stakeholders lined up to support a forward-looking outcome — from religious leaders to captains of industry.

Best-case outcome

On the other hand, the best-case outcome is not going to happen either. There are not going to be mitigation commitments on a sufficient scale to provide reasonable certainty that warming will be restricted to 2 degrees Celsius, never mind 1.5 degrees Celsius. In fact, adding up all the national commitments so far made — the Intended Nationally Determined Contributions — it is apparent that only 25 percent of the cuts needed have been promised. If additional cuts are not delivered in short order, the world is on track for warming of 3.5 degrees Celsius.

In a parallel universe, leaders would arrive in Paris ready to declare further reductions. Leaders from developed countries would also offer large amounts of additional finance, including for managing the loss and damage from historical emissions, new commitments on technology, and agreement to a treaty with legal force, full accountability and sanctions for nonperformance. They won’t do this.

The negotiations are too complex, the domestic politics too difficult. Do not expect a rabbit from a hat.

A marginally stronger or marginally weaker agreement

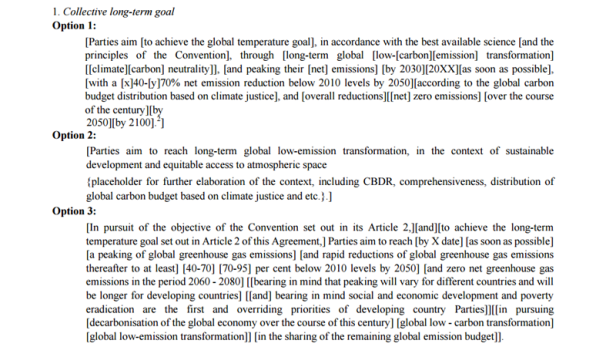

Between the best-case and worst-case outcomes lies the possibility of a marginally stronger or marginally weaker agreement. The outlines of these can be discerned by careful reading of the negotiating text, which currently runs to 52 pages and contains some 1,500 sets of square brackets and some 260 “options,” all referring to points which still need to be settled. Just as an example of the complexity, the box below contains the negotiating text of the key paragraph that describes the collective mitigation goal:

Source: Draft agreement and draft decision on workstreams 1 and 2 of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action

Buried in this mass of detail are a few key topics that are likely to exercise parties, and which could make for a stronger or weaker outcome: First, some will accept a long-term warming target of 2 degrees Celsius, while others — especially the most vulnerable countries — argue for 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Second, some will want faster and more regular reviews and opportunities to raise ambition.

Third, some will demand higher standards of accounting and accountability (so-called monitoring, reporting and verification).

Fourth, some will demand higher profile than others of loss and damage issues, opening the possibility of legal recourse.

Fifth, there will doubtless be arguments about money, including money for adaptation, in the context of the $100 billion promised by 2020.

Sixth, there may be an issue about the legal character of the agreement.

None of these topics is trivial. Indeed, whether warming is held to 1.5 degrees Celsius is of existential importance to some low-lying countries, which might well disappear if higher levels of warming produce the rise in sea levels that scientists predict.

The point, however, is that none of the issues is important enough at this point in time to derail the Paris agreement.

A departure point, not an endpoint

The reason is that Paris is a departure point, not an endpoint. Christiana Figueres has made this argument many times, and it is recognised in the negotiating text by an article on global stocktakes. That article (10) is only 20 lines long and has as many as 30 sets of square brackets, so it is not quite done and dusted — but, good news, there are no “options” that might eliminate it altogether.

In principle, therefore, there will be regular reviews that will enable all the difficult questions to be revisited. By the time of the first review, there may well be enough progress on the ground to facilitate ratcheting up of ambition. This is an optimistic conclusion. In the end, the diplomatic process has fulfilled its principal function, bringing all countries together in shared recognition that “something must be done.”

It was probably always unrealistic to imagine that countries would sign up to public commitments that they might or might not be able to meet. Instead, the process has created a platform and incentivized change in the real world. That is a real success. The challenge facing countries and all other actors is then to respond to the incentive Paris will provide.

At the Climate and Development Knowledge Network, working globally and in over 70 developing countries, we have learned one thing for sure: Implementing climate plans will never be friction free. Leadership has to be supported. Interests have to be placated and compensated. Policy measures have to be rolled out at the right time and in the right sequence. Partnerships have to be built, within countries, between countries at similar levels of development, and between richer and poorer countries. And all this has to be achieved while simultaneously delivering the poverty reduction and other objectives enshrined in the new global goals. It can be done, however.

It is no coincidence that the airwaves pre-Paris are filled with stories of success, from the rollout of solar power to energy efficiency and the renewal of forests. Acting on climate change, it turns out, is an opportunity. Climate-compatible development needs a global agreement to accelerate progress, and the stronger the better. But it does not need a perfect agreement to reflect and reinforce a change process that has already begun.

There will be further opportunities in the near future, as the review process kicks in. That is why negotiators should accept our thanks, make life simple, do the deal in Paris, and allow us all to move forward.

Image: Youth action on climate change at COP21, Paris.